Abstract

Africans are the second largest group affected by HIV in Western Europe after men who have sex with men (MSM). This review describes and summarises the literature on social, behavioural, and intervention research among African communities affected by HIV in the UK and other European countries in order to make recommendations for future interventions. We conducted a keyword search using Embase, Medline and PsychInfo, existing reviews, ‘grey literature’, as well as expert working group reports. A total of 138 studies met our inclusion criteria; 31 were published in peer-reviewed journals, 107 in the grey literature. All peer-reviewed studies were observational or “descriptive,” and none of them described HIV interventions with African communities. However, details of 36 interventions were obtained from the grey literature. The review explores six prominent themes in the descriptive literature: (1) HIV testing; (2) sexual lifestyles and attitudes; (3) gender; (4) use of HIV services; (5) stigma and disclosure (6) immigration status, unemployment and poverty. Although some UK and European interventions are addressing the needs of African communities affected by HIV, more resources need to be mobilised to ensure current and future interventions are targeted, sustainable, and rigorously evaluated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since its introduction in 1996, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for HIV infection has resulted in major reductions in morbidity and mortality in developed countries (Mocroft et al., 2003). However, access to treatment remains problematic in many parts of the world: 63% of people with HIV/AIDS live in sub-Saharan Africa, where HAART is available to just 23% of those who need it (UNAIDS, 2006; World Health Organisation, 2006). People of sub-Saharan African origin also suffer a disproportionate burden of HIV disease in Western Europe, where they are the second largest group affected by HIV after men who have sex with men (MSM). Over half of new HIV infections diagnosed in the EU in 2005 were acquired through heterosexual transmission. Half of these heterosexual infections were diagnosed in people of sub-Saharan African origin (Hamers, Devaux, Alix, & Nardone, 2006). Africans represent an increasing proportion of new HIV diagnoses in Germany (14%), Sweden (42%), France (27%), Belgium (35%), and the UK (32%) (Hamers & Downs, 2004; Health Protection Agency, 2004). In France, one in three persons newly diagnosed with HIV in 2004 was from sub-Saharan Africa (Le Vu, Lot, & Semaille, 2005). It is therefore essential that we appraise current research on African communities affected by HIV in Europe in an effort to enhance prevention strategies to support these population groups.

Africans living in Western Europe have highly diverse backgrounds (in this review we use the term ‘African’ to refer to people of sub-Saharan African origin, both recent migrants as well as second and third generation migrants). Many European countries are home to ‘established’ African communities (e.g. the Malian and Senegalese communities in France), as well as more recent ones (e.g. Zimbabwean migrants in the UK), leading to great socio-economic heterogeneity within African populations in individual European countries. Furthermore, African migration to Western Europe is a multifaceted phenomenon with complex causes. Many African migrants arrive in Europe in search of educational and employment opportunities, to be reunited with family, or to seek political asylum (International Organisation for Migration, 2005). While it is important to consider the situation of Africans affected by HIV and living in Europe ‘overall,’ it remains critical to assess the needs of particular African groups and communities within the context of individual countries’ frameworks and practices. In addition, European countries have different laws and practices concerning HIV testing and treatment for migrants, and this may impact on testing and access to care within African communities.

The literature highlights a number of features that commonly characterise the experience of Africans living with HIV in European countries: (1) African adults residing in Europe often discover their HIV status at a more advanced stage of disease progression, with lower CD4 counts at diagnosis, and, increasingly, with tuberculosis co-infection (Del Amo et al., 1996b; Delpech et al., 2004; Health Protection Agency, 2006); (2) they often face difficulties related to immigration status, social isolation, discrimination and HIV stigma, all of which act as barriers to accessing healthcare and social services (AIDS and Mobility, 2003; Kesby, Fenton, Boyle, & Power, 2003; Sigma Research and National AIDS Trust, 2004); (3) Africans living with HIV suffer from high levels of unemployment and poverty (Chinouya & Davidson, 2003; Elford, Ibrahim, Bukutu, & Anderson, 2007; National AIDS Trust, 2004).

Given these findings, there is a clear need for interventions to promote HIV testing and improve access to care among African communities in Western Europe. This requires primary prevention interventions to protect those at risk, and secondary prevention interventions to improve the lives of those living with HIV. But while the need for innovative interventions is evident, little is known about the effectiveness of existing HIV prevention interventions with African communities in a European context. Nor is much known about the social and behavioural factors that might influence the acceptability and feasibility of these interventions. This review aims to survey and describe social, behavioural and intervention research, both quantitative and qualitative, undertaken among Africans in European countries.

Search Strategies

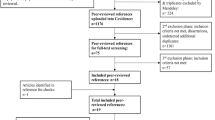

We performed a search of the databases Embase, Medline, and PsychInfo in November 2005, using combinations of the following words: ‘HIV’, ‘migrant’, ‘migration’, ‘sub-Saharan’, ‘ Black African’, ‘Africa’, ‘UK’ and ‘Europe’. A search for studies in progress was conducted using the UK National Research Register and the Cochrane Library. We also hand-searched retrieved articles, bibliographies of selected papers, ‘grey literature’, and expert working group reports from the UK and other European countries using the same keywords within internet search engines. Individual researchers from UK institutions were contacted to obtain access to unpublished studies. Grey literature was defined as reports from community-based organisations and research institutions, as well as conference abstracts and information about individual interventions available through keyword searches on the internet. In the absence of peer-review, publications were considerate adequate for inclusion in the study if the methodological approach used was clearly described, and, in the case of intervention reports, if the components of the intervention under consideration were clearly identified. Annual reports of community-based organisations and reviews published by institutions were also considered appropriate for inclusion in the study.

The review includes two broad types of studies relating to Africans affected by HIV in the UK and other European countries: (1) “Intervention studies”, including studies that described the planning phase of an intervention; (2) “Descriptive studies”, or observational, social, economic and behavioural studies, both quantitative and qualitative. Only studies published between 1996 (when HAART became available) and November 2005 were included, with no restriction on language, study design, or outcome under consideration. Literature from across Europe was included as many studies highlighted similarities in the challenges faced by Africans living with HIV in different European contexts.

Results and Discussion

A total of 138 studies met our inclusion criteria. The majority of these (107) were ‘grey’ publications, i.e. reports from governmental and non-governmental organisations, online materials, and conference abstracts. There were 31 descriptive studies published in peer-reviewed journals concerned with social, economic and behavioural research. Twenty-seven of these were quantitative (Table 1). We found no studies published in peer-reviewed publications describing interventions with migrants from sub-Saharan African countries. However, our search found details of 36 interventions addressing the needs of African communities affected by HIV in the grey literature (Tables 2 and 3).

In the following section of this paper we explore six key themes that emerged from the descriptive studies reviewed: (1) HIV testing; (2) sexual lifestyles and attitudes; (3) gender; (4) use of HIV services; (5) stigma and disclosure (6) immigration status, unemployment and poverty.

Descriptive Studies

HIV Diagnosis and Late Presentation

Three main findings are reported by studies reviewed in this section: (1) a steady increase in the number of heterosexually acquired HIV infections among Africans in Europe; (2) a low uptake of HIV testing leading to late presentation; (3) the need for interventions to increase the uptake of voluntary counselling and testing (VCT).

Surveillance data from 12 Western European countries show a steady increase in the number of new diagnoses of heterosexually acquired HIV among people from countries with generalised epidemics, the majority of them in sub-Saharan Africa (Hamers & Downs, 2004). In the UK for example approximately 21,500 Africans were living with HIV in 2005, of which approximately one third were undiagnosed (Health Protection Agency, 2006).

Throughout Western Europe, people of sub-Saharan African origin tend to present at a more advanced stage of disease, resulting in poorer prognosis (Del Amo, Bröring, & Fenton, 2003; Manfredi, Calza, & Chiodo, 2001; Staehelin et al., 2003). An unlinked and anonymous seroprevalence survey undertaken among heterosexual attendees at seven genitourinary medicine clinics in London between 1999 and 2000 found that 1 in 16 women and 1 in 33 men born in sub-Saharan Africa were infected with HIV. In addition, 39% of those that were HIV positive remained undiagnosed after the visit (Sinka, Mortimer, Evans, & Morgan, 2003). Mayisha II, a UK study involving over 1000 African men and women, found that two-thirds of its HIV positive respondents were undiagnosed (Mayisha II, 2005). Such high levels of undiagnosed HIV infection make a powerful case for interventions emphasising the benefits of early testing (Burns, Fakoya, Copas, & French, 2001).

A number of factors may explain such low levels of HIV testing among Africans living in Europe. First, evidence suggests that some Africans may not feel at risk for HIV. In a UK study, Erwin, Morgan, Britten, Gray, and Peters (2002) found that only 28% of Africans surveyed suspected they were HIV positive before diagnosis (versus 41% of white patients). Similarly, a French survey established that, in 2004, only 4.5% of persons accessing free anonymous testing (n = 5330) were of African origin (Le Vu et al., 2005). Second, lack of information about sexual health services means that Africans often do not know where to access testing (Chinouya & Davidson, 2003; Chinouya, Musoro, & O’Keefe, 2003; Erwin & Peters, 1999; McMunn, Mwanje, & Pozniak, 1997; Traore, 2002). Third, uncertain immigration status is a powerful deterrent to seeking an HIV test and accessing care (Anderson & Doyal, 2004; Flowers et al., 2006; Maharaj, Warwick, & Whitty, 1996). Psychosocial pressures linked to immigration concerns and poverty may leave many Africans unable to cope with a positive diagnosis, as described by a qualitative study with people of sub-Saharan African origin living in France: ‘You don’t want to know if you have it, you want to carry on living as before. So you don’t test’ (Adage, 2002).

Studies consistently point toward the need for innovative approaches to promote Voluntary Counselling and Testing (Burns et al., 2001; Del Amo, Goh, & Forster, 1996a; Del Amo et al., 1996b; Erwin et al., 2002; Mayisha II, 2005). Stigma remains an important barrier to VCT and awareness campaigns are needed to increase the uptake of testing (Adage, 2002; Chinouya & Reynolds, 2001; Elam, 2004a, b; Erwin et al., 2002; Sigma Research, 2004). Interventions might also focus on providing culturally appropriate support to the newly diagnosed (Flowers, Rosengarten, Davis, Hart, & Imrie, 2005; Ohen, Hunte, & Wallace, 2004; Erwin & Peters, 1999; Malanda, Meadows, & Catalan, 2001). Promoting innovative and effective paths to HIV testing remains one of the most important goals of prevention interventions for African communities in Europe.

Sexual Lifestyles and Attitudes

Studies reviewed in this section highlight that low condom use, low self-perceived risk for HIV, and the importance of notions such as fidelity and monogamy are characteristics of African communities affected by HIV in Europe (Erwin et al., 2002; Fenton, Chinouya, Davidson, Copas, & MAYISHA study team, 2002).

Studies report that while condom use among Africans living in Western Europe is often higher than in the general population, it is low in relation to the risk of HIV in African communities. In France, a survey of 5,398 Africans found that 62% used condoms only ‘occasionally’ with casual partners (Le Vu et al., 2005). In the UK, only 56% of 124 African respondents living with HIV interviewed in London consistently used condoms, while 43% used them sometimes or never (Chinouya et al., 2003). In a Dutch study, 82% of 537 Surinamese, Antillean, and African men and women reported inconsistent condom use in primary partnerships and 25% in casual partnerships (Wiggers, de Wit, Gras, Countinho, & van den Hoek, 2003). Similarly, in a north London study of 214 HIV positive African respondents, 40% of participants who had had sex in the previous month reported using a condom only on some occasions, while 29% had had unprotected sex (Fenton et al., 2002; Chinouya & Davidson, 2003). In another UK study, only 49% of men and 30% of women reported using a condom the last time they had sex (Mayisha II, 2005).

There is evidence that low condom use is related to expectations of fidelity, and qualitative studies have shown that Africans often feel condoms imply a lack of trust between partners (Elam, Fenton, Johnson, Nazroo, & Ritchie, 1999; Mayisha II, 2005). Respondents in a Portuguese study talked about culturally mediated reservations regarding condoms, for example the notion that “flesh on flesh is better” (Dias, Gonçalves, Luck, & Jesus Fernandes, 2004). In a UK study, respondents concurred that condom use was not appropriate or necessary in long-term relationships, and that it was seen as implying partner distrust (Mayisha II, 2005). Interviews with Africans living in France revealed that those who had multiple sexual partners used condoms, while couples in exclusive relationships felt it was unnecessary and implied promiscuity: “I am trusting, I know his life, he doesn’t hang around with people like that. We’ve been together for years, there’s no problem...” (Adage, 2004: 2). Similarly, Elam et al.’s study (1999) reports that serial monogamy is the favoured and expected pattern among African and Caribbean women in the UK, with women viewing multiple partnering as ‘physically and emotionally risky’. Furthermore, studies have reported that Africans may believe risk can be avoided by carefully choosing one’s partners (Elam, 1999; Mayisha II, 2005). This may be linked to the belief that belonging to the same ‘community’, whether nationally, regionally or religiously, is an assurance of ‘safe’ status. However, such culturally mediated assessments of risk remain poorly understood and documented in the literature. Similarly, the role of faith-based organisations in providing guidance and support about issues related to sexual lifestyles remains largely unexamined in the intervention literature, despite being mentioned in descriptive studies (Doyal & Anderson, 2005).

The culturally prescribed emphasis on monogamous relationships also belies a more complex reality. While respondents in two UK studies emphasised serial monogamy as the preferred type of relationship (Chinouya, Davidson, & Fenton, 2000), 22% of positive men and women interviewed in a North London study reported that their most recent partner was a casual one (Chinouya & Davidson, 2003). Furthermore, there is increasing evidence from European studies that some African migrants start new sexual relationships when travelling back to their home countries (Dias et al., 2004; Fenton, Chinouya, Davidson, & Copas, 2001; Kramer et al., 2005). Consequently, there is a need to understand the diversity of sexual lifestyles among Africans affected by HIV, and the ways in which issues of religious belief, gender, and migration underpin sexual decision-making and health-seeking behaviour.

Gender

Issues related to gender permeate discussions of HIV prevention and sexual risk behaviour among African communities in Europe. African women are over-represented among new heterosexual infections. In 2004, 57% of newly diagnosed HIV heterosexual infections in Western Europe were in women (WHO, 2005). This may be due to the high uptake of voluntary antenatal HIV testing by pregnant women in the 1990s and therefore conceal under-diagnosis in men (Coulon & Feroni, 2004; Gibb et al., 2004).

Particular issues affect African women living with diagnosed HIV in Western Europe. Studies show that the desire to have children is likely to be a key factor in positive women’s sexual decision-making, as many positive African women consider motherhood to be an important ‘source of identity and legitimacy’ (Doyal & Anderson 2005: 1731; Flowers et al., 2006; Ikambere, 2004). An African mother testifying at an HIV forum in Switzerland explains (Serena, 2005):

‘Thinking of my children’s well-being was my strength to go on [...] ‘with the help of my doctor, I decided to tell my children [...] what a relief! After so many years of keeping the secret from my children and hiding the medication’.

Migrant African mothers living with HIV are deeply affected by poverty, poor housing, and racism (Anderson & Doyal, 2004; MacLeish, 2002; Onwumere, Holttum & Hirst, 2002). There also remains a critical lack of interventions that support HIV positive parents or focus on the needs of children and adolescents growing up in families affected by HIV (Chinouya Mudari & O’Brien, 2005).

Studies also consistently highlight the need to put African men ‘back in the prevention picture’. African men report high levels of sexual risk behaviour (Fenton et al., 2005), and while they are visible in social venues such as bars and clubs, they are less often present in settings where HIV prevention is discussed (Chinouya & Reynolds, 2001). Some authors have suggested that the socio-economic difficulties faced by men as a result of migration often lead to a renegotiation of their roles as husbands, partners, and fathers, affecting decision-making and sexual risk-taking (Chinouya Mudari & O’Brien, 2005; Elam et al., 1999). Chinouya and Reynolds (2001) also comment that some men perceive HIV prevention gatherings as being primarily focused on women’s needs, children, relationships, and contraception. HIV prevention interventions should therefore take into account the needs of men and encourage them to participate in prevention programmes and activities.

Finally, there is a dearth of research on the sexual health and HIV prevention needs of African MSM. Twenty percent of men interviewed in a North London survey of HIV positive Africans said they had sex with another man in the year prior to interview, which would indicate that MSM constitute a small but significant portion of the African community in the UK. Recent evidence also suggests that black and ethnic minority MSM are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS. A study using UK national HIV prevalence data estimates that 7% of black and ethnic minority MSM living in the UK in 2002 were diagnosed with HIV, compared with 3% of white MSM (Dougan et al., 2005); Hickson, Reid, Weatherburn, Nutland, and Boakye (2004), working on the basis of self-reported data, show that 18% of black MSM were living with diagnosed HIV in the UK in 2004 compared with 10% of white MSM. However, HIV prevention is hampered by the fact that African MSM often shoulder stigma both from the African community and the predominantly white gay community (Fenton, White, Weatherburn, & Cadette, 1999). More research is required to understand the sexual health needs of African MSM and the best ways to reach them with prevention interventions.

Use of HIV Services

Studies exploring experiences of HIV care among Africans living in Western Europe report difficulties in accessing services due to barriers created by stigma, lack of information about services, as well as linguistic and immigration problems (Doyal & Anderson, 2005; Erwin & Peters, 1999; Mayaux, Teglas, & Blanche, 2003; Staehelin et al., 2003). These studies also confirm the continuing need for HIV information among Africans living in Western Europe. In Dias et al.’s Portuguese study (2004) of African migrants in Lisbon (n = 524), 31% of respondents thought that HIV could be transmitted through the use of public baths, and 28% through kitchen utensils. Similarly, 16% of Africans living with HIV in a London study felt they could be cured of HIV, while 8% thought an undetectable viral load meant they could not pass on the infection to anyone else (Chinouya & Davidson, 2003). Another UK study found that, compared with other people living with HIV in the UK, Africans were eight times more likely to report a need for more information about anti-HIV treatments (Weatherburn, Ssanyu-Seruma, & Hickson, 2003). There also remains a continuing need for information about HIV services. Researchers in the Ubuntu-Hunhu project in Hertfordshire (England) noted that 75% of African respondents were not able to mention a place where they could access free condoms, and that 65% did not know where to go for a sexual health checkup, including an HIV test.

Voluntary counselling and testing in primary care is increasingly considered an appropriate way to encourage early diagnosis of HIV among recent migrants, many of whom often do not suspect they may be infected (Medical Foundation for AIDS and Sexual Health, 2005; Ministère de la Santé, et de la protection sociale, 2004). McMunn, Mwanje, Paine, & Pozniak UK study (1998) demonstrated that Ugandan migrants felt GP surgeries were the most appropriate place to receive information about HIV. Similarly, 80% of Africans surveyed in Erwin et al.’s study (2002) had consulted a GP before testing. Interventions might therefore focus on improving the provision of HIV information and VCT in primary care.

Stigma and Disclosure

Throughout Europe, there remains overwhelming evidence of discrimination against HIV-positive people. Stigma and discrimination impede disclosure and deter people from accessing care and applying for work, thereby contributing to social exclusion. The impact of stigma on the lives of African people living with HIV is multifaceted. Respondents interviewed in focus groups in the UK reported numerous experiences of racism and discrimination; they also talked about stigmatising attitudes from doctors and healthcare staff, being concerned about confidentiality breaches and about HIV-related stigma within their own communities (Sigma Research and National AIDS Trust, 2004).

Fear of stigma may cause persons living with HIV to refrain from disclosing their status to sexual partners, children, friends, and to the broader community (Chinouya & Reynolds, 2001; Sigma Research and NAT, 2004); many HIV positive people feel unable to access community and social support groups because of the fear of disclosing their HIV status (Flowers et al., 2006). Africans living in close-knit communities, in particular, face difficulties in managing disclosure on their own terms. Storing antiretroviral medications at home and taking them at fixed times can lead to involuntary disclosure. Respondents in Flowers et al.’s study (2006) felt that certain ‘signs’, such as lipodystrophy or breastfeeding avoidance, automatically revealed their status. Africans testing for HIV at a London hospital were found to be twice as likely as ‘white’ patients to be worried about future discrimination if they tested positive, and four times more likely to be worried about meeting someone they knew at the clinic (Erwin & Peters, 1999). Concern with stigma and discrimination explains why many HIV positive African respondents in McMunn et al.’s London-based study (1998) resolved to keep their HIV status secret. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to make recommendations for specific interventions to reduce stigma in African communities, some of the information interventions discussed later in this paper offer some examples of successful and evaluated strategies (Elam, 2004b).

Immigration Status, Unemployment and Poverty

Recent African migrants living with HIV in Europe are disproportionately affected by immigration problems, poverty, and unemployment (AIDS and Mobility, 2003; Creighton, Sethi, Edwards, & Miller, 2004; Lert, Obadia et al., 2004; Takura & Power, 2002; Weatherburn et al., 2003). Immigration concerns, in particular, make it difficult for service providers to involve them in HIV prevention. In the majority of western European countries, while asylum seekers awaiting a decision are granted access to free HIV testing and treatment, those who remain illegally are deprived of this right (AIDS and Mobility, 2003; All Party Parliamentary Group on AIDS, 2003). In France, access to National Medical Aid (Aide Médicale d’Etat) which in principle covers HAARTis gradually being restricted for people of uncertain immigration status (INVS, 2005). Although the WHO (2005) estimates that 90% of people living with HIV in western Europe have access to HAART, in many countries this is still dependent on immigration status: ‘HAART is making inequality in HIV care more visible, even in countries with free and universal access to antiretroviral drugs’ (Del Amo et al., 2003). This situation heightens the risk of driving the epidemic underground, as people of African origin living with HIV may be more concerned with immigration and socio-economic issues than about their HIV status (AIDS and Mobility, 2003): ‘I’m not worried about the virus—my worry is whether I will be allowed to remain here in this country’ (Flowers et al., 2006). In addition, researchers have consistently questioned the existence of ‘treatment tourism’, i.e. relocation for the purpose of accessing HIV services. The majority of positive migrants do not suspect their status and test relatively late; it is therefore unlikely that they arrive in Europe with a view to seek medical treatment (Erwin et al., 2002; Fenton et al., 2002; Forsyth, Burns, & French, 2005; Lot et al., 2004;Terrence Higgins Trust, 2001a, b).

Unemployment and under-employment are factors that critically affect the lives of HIV positive African migrants throughout Europe (AIDS and Mobility, 2003; Green & Smith, 2004). As many as 26% of African respondents in a large French study were unemployed (Le Vu et al., 2005). Chinouya, Ssanyu-Sseruma, and Kwok’s study 2003) found a 230% increase in HIV/AIDS cases between 1996 and 2000 in London, the majority of which were among African asylum seekers living on a statutory stipend of £36 (US $70)a week. Studies clearly show that the main problem for Africans living with HIV is ‘getting enough money to live on’ (Chinouya & Davidson, 2003; Weatherburn et al., 2003).

In the light of these findings, increasing access to employment must be a priority for secondary prevention interventions with Africans living with HIV. UK studies have shown that fewer than 20% of Africans living with HIV are employed, despite being well qualified (Chinouya & Davidson, 2003; Weatherburn et al., 2003). In a Portuguese study (Dias et al., 2004), Africans were principally employed in low-earning jobs such as construction or domestic work. Bhatt et al. (2000) argue that there is a large pool of under-employed people of African origin, which Chinouya and Reynolds (2001) contend would be a valuable resource in the development of community-led HIV prevention initiatives. Moreover, the potential benefits of finding or returning to work have been highlighted in a number of studies (Anderson & Doyal, 2004; Gordon et al., 2005). A positive African woman from the French organisation Ikambere talked about the benefits of starting work in plain words: ‘Look at that (...), I’m already starting to put on weight again!’ (Ikambere, 2004: 43).

Intervention Studies

Our search found details of 36 interventions addressing the needs of African communities affected by HIV, all of which were in the grey literature: 23 were UK-based, and 13 were developed in other European countries (Tables 2 and 3). In the UK, eight interventions (out of 23) were funded by local health authorities. Only four initiatives were secondary prevention interventions focusing on the needs of people living with HIV, all of them using support groups. Two interventions specifically targeted black MSM, while a further two focused on improving the employment prospects of people of sub-Saharan African origin. In other European countries, interventions ranged from broad pan-European efforts to raise HIV awareness to programmes generated through national prevention strategies and local community-based initiatives. Throughout Europe the main focus has been on information interventions to raise awareness of HIV/AIDS and increase knowledge of available services. Only three of the 13 interventions in other European countries were secondary prevention interventions for people living with HIV.

The interventions identified by this review have begun to meet some of the needs highlighted in the descriptive literature. For example, a number of interventions in the UK focus on raising HIV awareness among young Africans through peer exchange. Other interventions seek to empower Africans to gain skills and employment (Gordon et al., 2005; Ikambere, 2004). However, progress remains hampered by a lack of evaluation, which means that service providers and funders are unable to judge the effectiveness of individual interventions. Few interventions have been critically assessed for their impact, and none have been subject to rigorous evaluation such as randomised controlled trials. Furthermore, many of these interventions have been stand alone pilots, and few have been replicated or been shown to be sustainable. The need for evaluation and more careful reporting is particularly striking in European countries such as France, Belgium and Portugal, where Africans are over-represented among the newly diagnosed.

Conclusion

This review highlights important current research and intervention needs. First, VCT remains the most effective method to reduce high levels of undiagnosed HIV infection and must be promoted in innovative ways among African communities in Europe. Second, interventions must work in culturally acceptable ways to promote safer sex and knowledge of available sexual health services. Third, HIV prevention interventions should focus on three groups that have previously received little attention: young people, heterosexual African men, and African MSM. Secondary prevention programmes must also work towards understanding and meeting the psychosocial needs of African parents and their children. Furthermore, as black and ethnic minority MSM appear to be disproportionately affected by HIV compared with white MSM in Britain, attention must urgently be given to interventions combating stigma and emphasizing the benefits of safer sex among African MSM. Fourth, primary care practitioners must be involved in distributing HIV prevention materials and carrying out HIV testing. Guidelines on HIV testing and caring for people living with HIV in primary care are available and should be widely disseminated (Madge, Matthews, Singh, & Theobald, 2004). Finally, the most readily identifiable problem for Africans living with HIV in Western Europe remains poverty. Interventions that encourage gaining or returning to employment as well as dealing with stigma in the workplace are a priority. Comprehensive preparatory research, community involvement, and the use of findings from sexual health ‘needs and attitudes’ surveys can help guide the development, piloting, and evaluation of interventions to ensure their sustainability. Involving community-based organisations and informal African networks remains the key to designing effective interventions with Africans living with HIV.

References

Adage. (2002). Les freins au dépistage du VIH chez les populations primo-migrantes originaires du Maghreb et d’Afrique Subsaharienne – Synthèse de l’étude qualitative (pp. 1–4). Paris.

Anderson, J., & Doyal, L. (2004). Women from Africa living with HIV in London; a descriptive study. AIDS Care, 16(1), 95–105.

Arendt, G., & von Giesen, H.-J. (2003). HIV-1-positive female migrants in Northrhine-Westphalia-relevant but unfocussed problem? European Journal of Medical Research, 8(4), 137–141.

AIDS and Mobility. (2003). Access to care: Privilege or right? Migration and vulnerability in Europe. Woerden: European Project Health and Mobility.

All Party Parliamentary Group on AIDS. (2003). Migration and HIV: Improving lives in Britain. An inquiry into the impact of the UK nationality and immigration system on people living with HIV.

Bhatt, C., Phellas, C., & Pozniak, A. (2000). National African HIV prevention projects: Evaluation report. London: Enfield and Haringey Health.

Burns, F. M., Fakoya, A. O., Copas, A. J., & French, P. D. (2001). Africans in London continue to present with advanced HIV disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS, 15(18), 2453–2455.

Camden and Islington Health Authority. (1997). HIV prevention strategy 1997–2000, Working with African Communities in Camden and Islington. London: Camden and Islington Health Authority.

Camden and Islington Health Authority. (2000). The 1st National African communities HIV primary prevention conference, proceedings. Camden and Islington Community Health Services NHS Trust.

Castilla, J., & Del Amo, J. (2000). Epidemiología de la infección por VIH/SIDA en immigrantes y minorías étnicas en Espana. Secretaría des Plan Nacional sobre el SIDA.

Chinouya, M., Ssanyu-Sseruma, W., & Kwok, A. (2003). The SHIBAH report: A study of sexual health issues affecting Black Africans living with HIV in Lambeth, Southwark, and Lewisham. London: Health First.

Chinouya Mudari, M., & O’Brien, M. (2005). AIDS and African childhood in London. The paradox of African traditions and modern concerns on childhood. London. Online paper, accessed 09/02/05 at: ttp://www.cindi.org.za/papers/paper2.htm

Chinouya, M., Musoro, L., & O’Keefe, E. (2003). Ubuntu-Hunhu in Hertfordshire. Black Africans in Herts: Health and social care issues: A report on the action research intervention in the county. The Crescent Support Group.

Chinouya, M., & Davidson, O. (2003).The PADARE project: Assessing the health related knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of HIV Positive African Accessing Services in North Central London. London: African HIV Policy Network.

Chinouya, M., & Reynolds, R. (2001). HIV prevention and African communities living in England: A framework for action. London: National AIDS Trust.

Chinouya, M., Davidson, O., & Fenton, K. (2000). The Mayisha study: Sexual attitudes and lifestyles of migrant Africans in inner London. Horsham: Avert.

Chinouya, M., Fenton, K., & Davidson, O. (1999). The Mayisha study: The social mapping phase. Horsham: Avert.

Connell, M. (2001). Sexually transmitted infections among Black young people in South East London: Results of a rapid ethnographic assessment. Culture Health and Sexuality, 3, 311–327.

Coulon, M., & Feroni, I. (2004). Genre et santé: Devenir mère dans le contexte des multithérapies antirétrovirales. Sciences Sociales et Santé, 22(3), 13–40.

Creighton, S., Sethi, G., Edwards, S. G., & Miller, R. (2004). Dispersal of HIV positive asylum seekers: national survey of UK healthcare providers. British Medical Journal, 329, 322–323.

Department of Health. (2005). Government response to the health select committee’s third report of session 2004–2005 on new development in sexual health and HIV/AIDS policy, http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/11/62/53/04116253.pdf (accessed 09/08/05).

Department of Health, African HIV Policy Network & National AIDS Trust. (2004). HIV and AIDS in African communities: A framework for better prevention and care. London.

Department of Health. (2003). Renewing the focus: HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in the United Kingdom in 2002. London: Health Protection Agency.

Del Amo, J., Bröring, G., & Fenton, K. (2003). HIV health experiences among migrant Africans in Europe: How are we doing? AIDS, 17(15), 2261–2263.

Del Amo, J., Goh, B. T., & Forster, G. E. (1996a). AIDS defining conditions in Africans resident in the United Kingdom. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 7(1), 44–47.

Del Amo, J., et al. (1996b). Spectrum of disease in Africans with AIDS in London. AIDS, 10(13), 1563–1569.

Delpech, V., Antoine, D., Forde, J., Story, A., Watson, J., & Evans, B. (2004). HIV and Tuberculosis (TB) co-infections in the United Kingdom (UK): Quantifying the problem. International AIDS society conference 2004, Abstract 2169174.

Dias, S., Gonçalves, A., Luck, M., & Jesus Fernandes, M. (2004). Risco de Infecção por VIH/SIDA: Utilização-acesso aos Serviços de Saúde numa comunidade migrante. Acta Medica Portuguesa, 17, 211–218.

Dougan, S., Elford, J., Rice, B., Brown, A. E., Sinka, K., Evans, B. G., Gill, O. N., & Fenton, K. (2005). Epidemiology of HIV among black and ethnic minority ethnic men who have sex with men in England and Wales. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81(4), 345–350.

Doyal, L., & Anderson, J. (2005). My fear is to fall in love again...’ How HIV-positive African women survive in London. Social Science and Medicine, 60(8), 1729–1738.

Edubio, A., & Sabanadesan, R. (2001). African communities in Northern Europe and HIV/AIDS. Report of two qualitative studies in Germany and Finland on the perception of the AIDS epidemic in selected African minorities., http://www.map-tampere.fi/dokumentit/report_african_communities.pdf (Accessed 09/02/05)

Elam, G. (2004a). Perspectives on Terrence Higgins Trust’s HIV prejudice and discrimination poster campaign: Views of Barnet residents, African Business Owners and Their Customers. Report for Barnet PCT and Terrence Higgins Trust.

Elam, G. (2004b). Stoping stigma with Awaredressers: Views of Barnet’s residents, businesses and their customers on the Awaredressers Project. Report for Barnet Primary Care Trust and the Terrence Higgins Trust, March 2004.

Elam, G., Fenton, K., Johnson, A., Nazroo, J., & Ritchie, J. (1999). Exploring ethnicity and sexual health: A qualitative study of sexual attitudes and lifestyles of five ethnic minority communities in Camden and Islington. London: University College London.

Elford, J., Ibrahim, F., Bukutu, C., & Anderson, J. (2007). Sexual behaviour of people living with HIV in London: Implications for HIV transmission. AIDS, 21(Suppl. 1), S63–S70.

Erwin, J., Morgan, M., Britten, N., Gray, K., & Peters, B. (2002). Pathways to HIV testing and care by black African and white patients in London. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 78(1), 37–39.

Erwin, J., & Peters, B. (1999). Treatment issues for HIV positive Africans in London. Social Science and Medicine, 49, 1519–1528.

Evans, B. A., Bond, R. A., & MacRae, K. D. (1999). Sexual behaviour and sexually transmitted infection among African and Caribbean men in London. International Journal of STD/AIDS, 10(11), 744–748.

Fassin, D. (2000). Constructions et experiences de la maladie: une étude anthropologique et sociologique du sida des migrants d’origine africaine dans la région parisienne. Available from: http://www.inserm.fr/cresp

Fenton, K., Chinouya, M., Davidson, O., & Copas, A. (2001). HIV transmission risk among sub-Saharan Africans in London travelling to their country of origin. AIDS, 15, 1442–1444.

Fenton, K. A., Chinouya, M., Davidson, O., Copas, A., & MAYISHA study team. (2002). HIV testing and high risk sexual behaviour among London’s migrant African communities: A participatory research study. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 78, 241–245.

Fenton, K.A., Mercer, C.H., McManus, S., Erens, B., Byron, C.J., Copas, A.J., Nanchahal, K., MacDowall, W., Wellings, K., & Johnson, A.M. (2005). Sexual behaviour in Britain: Ethnic variations in high-risk behaviour and STI acquisition risk. Lancet, 365, 1246–1255.

Fenton, K., White, B., Weatherburn, P., & Cadette, M. (1999). What are you like? Assessing the sexual health needs of Black gay and bisexual men. London: Big Up.

Flowers, P., Davis, M., Hart, G., Rosengarten, M., Frankis, J., & Imrie, J. (2006) Diagnosis, stigma and identity among HIV positive Black African living in the UK. Psychology and Health, 21(1), 109–122.

Flowers, P., Rosengarten, M., Davis, M., Hart, G., & Imrie, J. (2005). The experiences of HIV positive black Africans living in the UK. Working paper (forthcoming).

Forsyth, S., Burns, F., & French, P. (2005). Conflict and changing patterns of migration from Africa: The impact on HIV services in London, UK. AIDS, 19, 635–637.

Gibb, D. M., et al. (2004). Decline in mortality in Children with HIV in the UK and Ireland. British Medical Journal, 328, 524.

Gordon, B., Hudson, M., & Mansour, J. (2005). Getting the message out: An evaluation of equal 1 action 3: Mainstreaming. Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion, January 2005. Available from the Positives Futures Partnership.

Gras, M. J., Weide, J. F., Langendam, M. W., Coutinho, R. A., & van den Hoek, A. (1999). HIV prevalence, sexual risk behaviour and sexual mixing patterns among migrants in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. AIDS, 13(14), 1953–1962.

Green, G., & Smith, R. (2004). The psychosocial and health care needs of HIV-positive people in the United Kingdom following HAART: A review. HIV Medicine, 5(Suppl.1), 5–46.

Hamers, F. F., Devaux, I., Alix, J., & Nardone, A. (2006). HIV/AIDS in Europe: Trends and EU-wide priorities. Euro Surveill 2006;11(11):E061123.1. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2006/061123.asp#1

Hamers, F. F., & Downs, A. M. (2004). The changing face of the HIV epidemic in western Europe: What are the implications for public health policies? The Lancet, 364, 83–94.

Health Protection Agency. (2006). A complex picture: HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in the United Kingdom: 2006. Available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/publications/2006/hiv_sti_2006/contents.htm

Health Protection Agency. (2005). HIV and AIDS in the United Kingdom quarterly update: Data to the end of June 2005. Volume 15, Number 30.

Health Protection Agency. (2004). Populations at risk of HIV and STIs – Black and Ethnic minority populations, Updated November 2004. Availablefrom:http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics _az/hiv_and_sti/populationsatrisk/groups/ethnicminorities.htm

Health Protection Agency. (2003). Focus on prevention: HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in the United Kingdom in 2003. An update: November 2004. London: Health Protection Agency, Centre for Infections.

Hickson, F., Reid, D., Weatherburn, P., Nutland, W., & Boakye, P. (2004). HIV, sexual risk and ethnicity among men in England who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 80, 443–450.

Ikambere. (2004). Rapport 2004. Paris. Available from: http://www.ikambere.com/rapport_2004.pdf

Institut de veille sanitaire. (2005). Épidémiologie du VIH/sida chez les migrants en France. Saint-Maurice: INVS.

International Organisation for Migration. (2005). World migration 2005: Costs and benefits of international migration, Vol. 3, IOM World Report Series.

Kesby, M., Fenton, K., Boyle, P., & Power, R. (2003). An agenda for future research on HIV and sexual behaviour among African migrant communities in the UK. Social Science and Medicine, 57(9), 1573–1592.

Kramer, M., Van Veen, M., Op de Coul, E., Van de Laar, M., Coutinho, R., Cornelissen, M., & Prins, J. M. (2005). [Conference Abstract] Heterosexual HIV transmission among migrants from Surinam and the Netherlands Antilles: HIV prevalence, sexual risk, and the role of travelling to the country of origin. European Journal of Public Health, 15(1), 21–23.

Lert, F., Obadia, Y., & l’équipe de l’enquête VESPA. (2004). Comment vit-on en France avec le VIH/SIDA? Populations et Santé, Numéro 406, Novembre 2004.

Le Vu, S., Lot, F., & Semaille, C. (2005). Les migrants africains au sein du dépistage anonyme du VIH, 2004. BEH no. 46–47. Institut de Veille Sanitaire.

Lot, F., Larsen. C., Valin, N., Gouezel, P., Blanchon, T., & Laporte, A. (2004) Parcours Sociomédical des personnes originaires d’Afrique subsahararienne atteintes par le VIH prises en charge dans les hopitaux d’Ile-de-France, 2002. Bulletin études no. 5, 2004, p. 17. Institut de Veille Sanitaire.

Low, N., Paine, K., Clark, R., Mahalingam, M., & Pozniak, A. (1996). AIDS survival and progression in black Africans living in south London, 1986–1994. Genitourinary Medicine, 72, 1, 12–16.

Lyall, E. G. H., et al. (1998). Review of uptake of interventions to reduce mother to child transmission of HIV by women aware of their HIV status. British Medical Journal, 316, 268–270.

MacLeish, J. (2002). Mothers in exile. London: Maternity Alliance

Madge, S., Matthews, P., Singh, S., & Theobald, N. (2004). HIV in primary care. London: The Medical Foundation for AIDS & Sexual Health.

Maharaj, K., Warwick, I., & Whitty, G. (1996). An assessment of HIV prevention interventions with refugees and asylum seekers, with particular reference to refugees from the African continent. London: Health and Education Research Unit.

Malanda, S., Meadows, J., & Catalan, J. (2001). Are we meeting the psychological needs of Black African HIV-positive individuals in London? Controlled Study of referrals to a psychological medicine unit. AIDS Care, 13(4), 413–419.

Manfredi, R., Calza, L., & Chiodo, F. (2001). HIV disease among immigrants coming to Italy from outside of the European Union: A case–control study of epidemiological and clinical features. Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases, 127(3), 527–533.

Mayaux, M.-J., Teglas, J.-P., & Blanche, S. (2003). Characteristics of HIV-infected women who do not receive preventive antiretroviral therapy in the French perinatal cohort. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 34(3), 338–343.

MAYISHA II Collaborative Group. (2005). Assessing the feasibility and acceptability of community based prevalence surveys of HIV among black Africans in England. Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections: London.

McMunn, A., Mwanje, R., Paine, K., & Pozniak, A. L. (1998). Health service utilization in London’s African migrant communities: Implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care, 10(4), 453–462.

McMunn, A., Mwanje, R., & Pozniak, A. L. (1997). Issues facing Africans in London with HIV infection. Genitourinary Medicine, 73(3), 157–158.

Medical Foundation for AIDS and Sexual Health. (2005). Recommended standards for health services. Available online at: http://www.medfash.org.uk/publications/documents/Recommended_standards_for_sexual_health_services.pdf. Accessed 12/05/05.

Ministère de la Santé et de la protection sociale. (2004). Programme National de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA en direction des étrangers/migrants vivant en France (2004/2006). Paris.

Mocroft, A., Ledergerber, B., Katlama, C., Kirk, O., Reiss, P., D’Arminio Monforte, A., Knysz, B., Dietrich, M., Phillips, A., & Lundgren, J. (2003). Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: An observational study. The Lancet, 362(9377), 22–29.

National AIDS Trust. (2004). Annual report 2003–4. London.

National African HIV Prevention Programme: Pulle, S., Lubega, J., Davidson, O., & Chinouya, M. (2005). Doing it well: A good practice guide for choosing and implementing community-based HIV prevention interventions with African communities in England. London.

National African HIV Prevention Programme. (2004). 3rd National African HIV prevention conference report. What next? The future of HIV prevention with African communities, 11–12 March 2004. London.

Ohen, L., Hunte, S., & Wallace, C. (2004). Who provides social advice to HIV positive clients? London: Lambeth Primary Care Trust.

Onwumere, J., Holttum, S., & Hirst, F. (2002). Determinants of quality of life in black African women with HIV living in London. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1, 61–74.

Project Nasah. Briefing sheet 1 and 2. Available Online: http://www.sigmaresearch.org.uk/downloads/nasahbriefing.pdf

Sasse, A., Vincent, A., & Galand, M. (2002). High HIV prevalence among patients choosing anonymous testing. International AIDS society conference, Abstract, 9092.

Serena, L. (2005). Testimony of Lucy. Forum Sida Suisse 2005, http://www.aids.ch/f/forum/pdf/migration/TESTIMONY%20OF%20LUCY.pdf

Sigma Research and NAT. (2004). Outsider status – Stigma and discrimination experienced by Gay men and African people with HIV. London: Sigma – NAT.

Sigma Research. (2002). National survey of people living with HIV. London.

Sigma Research: Ndofor-Tah, C., Hickson, F., Weatherburn, P., Amamoo, N.A., Majekodunmi, Y., Reid, D., Robinson, F., Sanyu-Sseruma, W., & Zulu, A. (2000). Capital assets. London.

Sinka, K., Mortimer, J., Evans, B., & Morgan, D. (2003). Impact of the HIV epidemic in sub-saharan Africa on the pattern of HIV in the UK. AIDS, 17, 1683–1690.

Staehelin, C., Rickenback, M., Low, N., Egger, M., Lederberger, B., Hirschel, B., d’Acremont, V., Battegay, M., Wagels, T., Bernasconi, E., Kopp, C., & Furrer, H. (2003). Migrants for sub-Saharan Africa in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: Access to antiretroviral therapy, disease progression and survival. AIDS, 17(15), 2237–2244.

Study group for the MRC collaborative study of HIV infection in women. (1996). Ethnic differences in women with HIV infection in Britain and Ireland. AIDS, 10(1), 89–93.

Takura, D., & Power, L. (2002). Establishing initial peer support and services for migrant African women in Birmingham, UK. International AIDS society conference, Abstract 1821.

Terrence Higgins Trust, Doyal, L., & Anderson, J. (2003). My heart is loaded. African women with HIV surviving in London, a research report. London.

Terrence Higgins Trust. (2001a). Prejudice, discrimination and HIV. London.

Terrence Higgins Trust. (2001b). Social exclusion and HIV. London

Traore, C. (2002). Promoting knowledge of HIV Status amongst Africans in the UK. International AIDS society conference, Abstract 9597.

UNAIDS. (2006). AIDS epidemic update: Global summary. Available from: http://www.data.unaids.org/pub/EpiReport/2006/02-Global_Summary_2006_EpiUpdate_eng.pdf

UNFPA, UNAIDS and UNIFEM. (2004). Women and HIV/AIDS: Confronting the crisis. UNFPA, UNAIDS and UN.

Weatherburn, P., Ssanyu-Seruma, W., & Hickson, F. (2003). Project NASAH: An investigation into the HIV treatment, information and other needs of African people with HIV resident in England. Sigma Research, NAM Publications, National AIDS Trust and African HIV Policy Network.

Wiggers, L. C., de Wit, J. B., Gras, M. J., Countinho, R. A., & van den Hoek, A. (2003). Risk behavior and social-cognitive determinants of condom use among ethnic minority communities in Amsterdam. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15(5), 430–447.

World Health Organisation. (2006). Towards universal access by 2010: How WHO is working with countries to scale-up HIV prevention, treatment, care and support.WHO, October 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/advocacy/universalaccess/en/index.html

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prost, A., Elford, J., Imrie, J. et al. Social, Behavioural, and Intervention Research among People of Sub-Saharan African Origin Living with HIV in the UK and Europe: Literature Review and Recommendations for Intervention. AIDS Behav 12, 170–194 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9237-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9237-4