Abstract

HIV treatment initiatives have focused on increasing access to antiretroviral therapy (ART). There is growing evidence, however, that treatment availability alone is insufficient to stop the epidemic. In South Africa, only one third of individuals living with HIV are actually on treatment. Treatment refusal has been identified as a phenomenon among people who are asymptomatic, however, factors driving refusal remain poorly understood. We interviewed 50 purposively sampled participants who presented for voluntary counseling and testing in Soweto to elicit a broad range of detailed perspectives on ART refusal. We then integrated our core findings into an explanatory framework. Participants described feeling “too healthy” to start treatment, despite often having a diagnosis of AIDS. This subjective view of wellness was framed within the context of treatment being reserved for the sick. Taking ART could also lead to unintended disclosure and social isolation. These data provide a novel explanatory model of treatment refusal, recognizing perceived risks and social costs incurred when disclosing one’s status through treatment initiation. Our findings suggest that improving engagement in care for people living with HIV in South Africa will require optimizing social integration and connectivity for those who test positive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

South Africa holds a unique position globally, having the largest number of people living with HIV in the world, estimated at 6.3 million as of 2013 [1]. The country has also been the single largest recipient of funding from the President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has helped underwrite the cost of care for 2.5 million South Africans currently in treatment [2, 3]. Despite South Africa’s implementation of the world’s largest antiretroviral treatment (ART) program [4], only a third of the over 6 million people living with HIV are actually in care [5]. Those who do choose to initiate ART often have very low CD4+ cell counts and high rates of co-morbidities, such as tuberculosis or other opportunistic infections, putting them at exceedingly high risk of early mortality [6]. The goal of achieving population-level reductions in the transmission of HIV in South Africa will not be achieved until all ART-eligible individuals are actually on treatment [7], and people living with HIV no longer wait to start ART until they have symptoms of advanced AIDS [6, 8].

There is expanding literature focused on understanding why millions of ART-eligible individuals in South Africa are not engaging in care [6, 9–11]. This is particularly relevant in light of increasing evidence of the importance of treatment in individuals living with HIV as a form of prevention to uninfected partners [12–14]. Now with a shift in funding allocations from PEPFAR, and a move towards decentralization of care [15], there is a greater need to understand how to engage individuals living with HIV in a timely manner to avoid potential treatment delays [2].

We previously identified treatment refusal as an important cause of failure to link to care [16]. Our initial findings in a cohort of individuals presenting for testing in Soweto showed that 20 % of those who qualified for treatment refused to initiate ART, and the leading reason for ART refusal was given as “feeling healthy” (37 %), despite clients having a median CD4+ cell count of 110 cells/mm3 and triple the rate of active tuberculosis as seen in non-refusers. Other groups have now recognized the impact of ART refusal on engagement in care [11, 17–21].

These early findings suggest that people living with HIV may have a subjective feeling of health and wellness that is not intrinsically related to their actual clinical status. Understanding factors that drive treatment refusal will help identify at-risk individuals and strategies for effective, targeted interventions to improve linkage to HIV treatment and care. This research is essential to prevent what may be an early roadblock to “test and treat” strategies aimed at improving ART initiation and outcomes by offering immediate ART to individuals upon testing positive. We undertook this qualitative study at the site of our prior research in Soweto, South Africa to inductively identify reasons for ART refusal from patients’ and providers’ perspectives, and develop a comprehensive explanation of why patients who presented to an urban voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) center refused to initiate treatment.

Methods

Study Design and Overview

We performed a qualitative, patient and provider focused study using semi-structured interview guides. Our goal was to understand why adults who presented for testing and learned they were HIV positive and eligible for ART, ultimately refused to initiate treatment. Qualitative research allowed us to gain a deeper conceptual understanding of an under-studied phenomenon, and provide a basis for developing our explanatory model of ART refusal.

Study Site

Zazi Testing Center is a VCT center affiliated with the Perinatal HIV Research Unit and Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto, South Africa. Baragwanath is third largest hospital in the world, serving the entire population of Soweto [22]. Individuals presenting for VCT sign a consent form, have blood drawn, and receive a rapid HIV test. Approximately 35 % of clients test positive for HIV. Those who test positive are asked to return 1 week later for CD4+ results and referred for treatment as appropriate. The current South African Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines recommend treatment for any individuals whose CD4+ count ≤350 cells/mm3 irrespective of WHO clinical stage, or anyone with tuberculosis or with WHO stage 3 or 4 irrespective of CD4+ count [23]. We chose this VCT clinic because it was the site of our prior research identifying ART refusal, and we felt it would provide the most focused understanding of this phenomenon.

Sampling and Recruitment

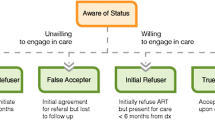

We used a purposive sampling strategy to select HIV positive adults who presented for VCT and were found to be treatment-eligible [24]. Our recruitment strategy was informed by research literature showing a range of treatment-related decision-making among adults accessing HIV testing in sub-Saharan Africa [25], and our understanding of clients presenting for testing at Zazi. Our goal was to represent a comprehensive spectrum of decision-making. To this end, we defined the following four groups: “Sustained refusers” were individuals who declined ART after learning they were eligible for treatment, and chose not to initiate ART for at least 6 months after testing; “False acceptors” initially agreed to start treatment, but failed to present for care within at least 6 months after learning of their treatment eligibility; “Initial refusers” declined ART when counseled at testing, but ultimately entered care within 6 months; and “True acceptors” were individuals who agreed to start ART at testing, and who shortly thereafter presented for care. Our purposive sampling strategy is represented schematically in Fig. 1.

Additionally, we interviewed health-service providers who worked at the testing center or the PEPFAR-funded treatment center, where most patients were referred, to gain insight into provider and delivery-level factors related to treatment refusal among adults who presented for testing. Service providers included counselors and social workers who delivered test results, as well as treatment providers. For this study, we chose to recruit a total of 50 participants in order to reach saturation in each subgroup.

Eligibility Criteria

ART decision-makers eligible for this study were: (1) age >18 years at the time of enrollment, (2) presenting for VCT at Zazi, (3) willing to have blood drawn for HIV testing and CD4+ count, (4) tested positive for HIV and found to be eligible for ART based on CD4+ criteria (CD4+ count ≤350 cells/mm3), (5) residents of Soweto, and (6) willing and able to give informed consent. Children and pregnant women were excluded, since they were enrolled in a separate HIV care program, which included more aggressive follow-up and linkage to care procedures than would be standard for routine adult care.

Eligibility criteria for medical and social-service providers included: (1) age >18 years, (2) direct contact with clients presenting for VCT or treatment, and (3) willing and able to give informed consent. Language spoken by the participant was not an exclusion criterion for this study.

Informed Consent

We designed the informed consent procedure for this study to maximize understanding of potential risks. To insure correct use of language, all consent forms were translated into Zulu and Sesotho, and back translated into English. In addition, the research assistant (RA) read consent forms aloud to participants. After reading the consent forms, she requested participants summarize the study and explain the reasons why they wanted to participate, prior to seeking a signature. Individuals were provided with information on how to contact the study staff to report adverse events or other concerns associated with the study.

As part of the informed consent process, participants were informed of how confidentiality of participation would be insured. Specifically, all data were coded by subject number. Paper copies of data were kept in locked cabinets and only provided to study personnel. Electronic data were de-identified and were stored in a secure, password protected site, only available to study staff. Interviewers and support staff were trained on procedures for maintaining privacy and signed a pledge of confidentiality. This study was approved by Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board, Boston, MA and University of Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee, Johannesburg, South Africa in October 2011. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Data Collection and Preparation

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews, in which questions were standardized but open-ended, were performed with participants between April 2012 and April 2013. All interviews took place in a private location at the testing center, and lasted approximately 60–90 min. Topics included:

-

(1)

Beliefs and experiences involving testing.

-

(2)

Experiences of learning one’s HIV status and qualifying for ART.

-

(3)

Beliefs regarding ART efficacy, side-effects, and the importance of adherence.

In addition to the standardized questions, we explored areas participants identified as relevant to their decision-making, including: religion and faith, stigma, fate, mental health, notions of health and wellness, and structural factors. Interviews were conducted by a trained RA in English, Zulu, or Sesotho, based on the choice of the participant. The RA underwent a detailed training with the primary author, and was supervised by the second author. The senior author, an expert in socio-behavioral research with over 20 years of experience performing qualitative research, provided guidance for study design and interviewer training.

We pilot-tested the interviews with a small group of eligible individuals in advance of recruiting our full sample to insure participants would have a full understanding of the questions posed in the interview. Participants for our pilot interview included both providers and ART-eligible individuals. The pilot test involved using our semi-structured interview guide to interview participants. We gauged evidence of comprehension through a dialogue with the participant after the interview, as well as a review of transcripts by two authors (ITK and GT). All interviews were audio-recorded with permission, and were transcribed and translated to English. All transcripts were reviewed for quality by ITK, GT, and KR

Data Analysis

The goal of the analysis was to develop an explanatory model of treatment refusal based on participants’ reasons for accepting or declining ART treatment. Using a category construction approach, we began our inductive analysis with a detailed review of all the transcripts to identify factors related to ART refusal. We used open coding and memoing for our initial evaluation of the transcripts, in which interview data were repeatedly reviewed line by line to identify sections of text related to treatment decision-making [26]. We then moved into a deductive phase of coding, referred to as descriptive coding. For this phase, we were guided by our research question, and used QSR International’s NVivo 9 software to aid in organizing categories. We assigned labels to each category, and identified illustrative quotes from interview transcripts. We ensured trustworthiness of the data by having two authors participate in this process (ITK, KR).

We used the same process of data analysis for healthcare providers and adult VCT participants. Once we had identified our categories, we re-examined our data and developed broader concepts linking these categories. We ultimately developed an explanatory model of treatment refusal, based on our findings. The categories supporting this model are presented below.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Ninety-nine individuals were identified as eligible to participate in the study upon review of clinic files, and 50 agreed to participate and were consented (51 %). We interviewed 43 ART-eligible adults (“patients”) presenting for testing at Zazi and 7 service providers. Of the 43 patients, 21 were women and 22 were men. Twelve were sustained refusers, 11 were false acceptors, 5 were initial refusers, and 15 were true acceptors. Of the seven care providers, three were women and four were men. Table 1 provides a summary of participant demographics.

Risks Perceived in Starting Treatment

Participants who refused to initiate treatment framed their concerns in a context of costs or risks associated with starting ART. These risks were categorized as follows.

Losing Health or Beauty

Participants who refused to start treatment often framed decisions related to their health and well-being. Many described feeling “too healthy” in the moment of decision-making to consider ART initiation (see Table 2, Quote 1). Being “healthy” and “beautiful” off of medication was often juxtaposed against visual and physiologic side-effects associated with being on certain types of treatment. Starting treatment was often described in graphic terminology related to body dysmorphic syndromes (“They change your shape, you will have a huge stomach and your arms look like weight lifters, and you will be ugly and dark in complexion”), and a decline in physical and mental health (“These tablets change people – they become dark and have nightmares and lose their mind”). Others associated starting treatment with a decline in health (“I was fine all along, but once I started the treatment, then I fell ill”) and a feeling of “heaviness” associated with lethargy, weakness, and general malaise.

Stigma Associated with Disclosure

Participants recounted stories of both internalized shame they felt living with HIV, and externalized stigma they experienced in their community. Often, participants’ views on being physically disfigured or mentally altered on medication compounded self-defeating beliefs, leading to demoralization and a desire to conceal one’s status, and not be seen in clinic (see Table 2, Quote 2). Terms such as “trackers” or “starters” were used to refer to people who initiated treatment, or continued on treatment, and were framed as being derogatory by participants. The mode of HIV acquisition often compounded participants’ internalized stigma (see Table 2, Quote 3). The need to stay integrated into one’s community, and the fear of social isolation that would result from an HIV diagnosis, often led participants to refuse to initiate treatment in order to avoid disclosure.

Increased Financial Burdens

Starting treatment was often viewed as an insurmountable challenge in a life already burdened with an inability to meet the basic needs of one’s family (see Table 2, Quote 4). Shame and stigma were often closely linked with poverty and it associated stressors (including food insecurity, unstable housing, and limited access to transportation to clinic). In poor communities, where neighbors often lived in close proximity to each other, participants often reported feeling ashamed and ultimately more stigmatized by the public nature of unwanted disclosures due to taking their medications. In addition, unstable housing often led participants to fear initiating treatment due to concerns about their ability to adhere (see Table 2, Quote 5).

Religious Mores

Participants described faith and God as guiding forces that informed decision-making. Participants who started treatment discussed how they believed God was a “healer,” but that starting medication was necessary since they were “of flesh and earth,” and that God could only heal “if you take your medication.” Conversely, those who chose not to initiate treatment also invoked spirituality and faith as a reason not to need treatment (see Table 2, Quote 6). Religious mores that centered on morality and a strong belief in God as a provider and healer were commonly invoked. While certain congregations appeared to support initiating treatment in the setting of a new HIV diagnosis, many participants discussed God as the larger force, and that HIV could be considered “a punishment” that only God has the power to cure.

Role of Traditional Healers and Alternative Therapies

Those participants who felt medications were associated with being sick, often used herbs and sought the counsel of traditional healers instead (see Table 2, Quote 7). Both accepters and refusers sought out “immuno-boosters” in the forms of vitamins, and other supplements. These were often recommended by friends and family members, either as a way to enhance treatment, or as a substitute for it (see Table 2, Quote 8). “Traditional medications”, prescribed by “witch doctors,” were often referenced as being a cure-all, and being a more natural form of therapy.

Protective Factors Offsetting Risks of Starting Treatment

Participants, particularly those who were willing to start treatment, identified multiple sources of support that offset the risks associated with treatment initiation.

Social Support

Participants who described having strong social support from family, allowing them to disclose their status, often were able to mitigate the challenges associated with starting treatment (see Table 2, Quote 9). This support was characterized as providing a sense of humanity (“I felt like I was human after all”) and a buffer against normative stigmatizing beliefs (see Table 2, Quote 10). Conversely, treatment refusers reported wishing for a community support system to allow them to discuss their concerns about their diagnosis and treatment (see Table 2, Quote 11).

Coping and Resilience

Coping emerged as a means by which participants attempted to manage stigma and move beyond perceived risks of starting treatment. Those who exhibited resilience in the face of a new HIV diagnosis often invoked their desire to live for others as a reason to overcome concerns about starting treatment (see Table 2, Quote 12). Many participants described living with adversity related to poverty, food insecurity, violence, and the stressors associated with volatile relationships or raising children alone, and called upon these inherent coping skills in order to initiate treatment (see Table 2, Quote 13). Ultimately, adaptive coping strategies that enabled participants to gain acceptance of their diagnosis mitigated the perceived risks associated with treatment initiation.

Positive Messages from Government or Media

Participants described ubiquitous HIV educational messaging coming from many sources—most notably the South Africa Government, and media, through educational soap operas and other forms of entertainment (see Table 2, Quote 14). Real life experiences of media personalities living with HIV provided messages on how to overcome concerns about starting treatment (see Table 2, Quote 15). Others who refused to initiate treatment felt less of a desire to engage in the messaging being presented (see Table 2, Quote 16).

Role of Healthcare Providers

Healthcare providers had the potential to moderate the risk of ART refusal by creating an environment that provided compassionate care for patients who were concerned about initiating treatment. Specifically, a strong therapeutic alliance with providers could establish a refuge from HIV-associated stigma, and instill an understanding of the importance of ART initiation. One provider described her encounter with a patient who refused to initiate ART because she was concerned about the potentially lethal effects of starting medication (see Table 2, Quote 17). Conversely, healthcare providers also recognized that clinic staff could contribute to patients’ sense of isolation, and feeling stigmatized (see Table 2, Quote 18).

Explanatory Model of Treatment Refusal

To integrate our core findings, we developed an explanatory model for understanding treatment refusal. One can best understand our model within a larger context of risk perception, which posits that people tend to make decisions about risks based on affect, stigma, or fear, and in general, are highly loss averse [27]. For individuals who choose not to initiate treatment, the perceived risk of starting treatment may ultimately outweigh the known life-saving benefits of being on medication.

Risk is embedded in an optimistic vision of one’s general health and well-being off of ART, and in concerns about the harmful effects of being on medication. These concerns may be anchored in the knowledge that many prior medications made available to people living with HIV were known to have disfiguring side-effects, leading to the possibility of an unwanted disclosure of one’s HIV-status. In communities where disclosure could lead to social isolation, starting treatment could be perceived as disrupting the fragile balance in which many people are living. Therefore in this context, avoiding treatment may be considered a safer alternative than initiating ART. Conversely, individuals who are able to draw upon social support to minimize the harmful effects of life stressors are able to capitalize on their inherent resilience, and overcome fears related to starting ART. These findings support a broader more subjective interpretation of perceived barriers to treatment initiation that recognizes both the importance of social support and its impact on affective and cognitive judgments [28].

Discussion

This qualitative study provides a novel understanding of why treatment-eligible adults may choose not to initiate ART. In our explanatory model, the decision to refuse treatment is based on an optimistic view of one’s own health, and a belief that starting medications can be inherently risky due to potentially disfiguring side effects, resulting in an unwanted disclosure and social isolation. This may lead to seemingly irrational choices to avoid detection until disease progression renders further concealment impossible.

Central to this model is the meaning of ART initiation for participants, and the common belief that people living with HIV initiate treatment when they are sick, instead of starting it while healthy. As such, participants experience starting treatment as an acknowledgement of poor health, and potentially their own mortality. Fears of side-effects associated with ART, stigma from being identified as “sick”, and concerns about one’s own inability to adhere to treatment often augment the perceived risks inherent to treatment initiation [29, 30]. Prior qualitative research in South Africa has similarly shown that ART has often been viewed as signifying AIDS and approaching mortality [11].

In this context, social support proves critical to enhancing participants’ ability to cope with the life changes that are required to overcome concerns related to ART side-effects, internalized and externalized stigma, potentially increased financial burdens, and the lure of seemingly safer alternative therapies. While little research has focused on the impact of social connectivity and adaptive coping on decision-making prior to ART initiation, social integration has been recognized as a core component of treatment adherence in resource-limited settings [31–33]. The importance of social support and integration are particularly salient in settings of extreme poverty where treatment barriers are highly prevalent [34–37] and social ties may be essential for survival [33, 38, 39], ultimately allowing people living with HIV to cope with internalized stigma [40].

People with early-stage disease are particularly at risk. First, they may not perceive the need for treatment because they have not yet experienced loss of physical function, a powerful motivator for behavior change [41]. Second, due to the stigmatized status of HIV infection in many resource-limited settings [40, 42–44], people living with HIV with full functional status might have less motivation to disclose their status [45–48]. Nam et al. also found that ill patients experience faster acceptance of their HIV status, which facilitates HIV disclosure and activates their social support network [49]. Green and Wagner found that HIV disclosure is closely associated with the degree of tangible support HIV+ people receive from their network [50]. Taken together, these findings suggest that people with early-stage disease might not disclose their HIV status, might not activate their social ties, and might not mobilize social support to overcome the common structural barriers to HIV care in resource-limited settings; this could result in sub-optimal engagement in care and failure to initiate ART.

In addition, socioeconomic barriers to care may impede engagement in care, as has been described previously, despite the widespread availability of free treatment through PEPFAR and the Department of Health clinics [51]. These findings suggest that existing ART programs may be more successful if coupled with economic incentives to initiate and adhere to treatment, since this may provide economic stability that is necessary for treatment initiation and retention in care.

Our study has several limitations. First, within our purposively sampled targeted groups, we were limited to a convenience sample of patients who could be located and were willing to be interviewed; thus, our data may not capture the reasons for ART refusal among people who could not be located, or who were not willing to be interviewed. In addition, our data may not capture reasons for ART refusal in other locations in South Africa. Future studies should examine reasons for treatment refusal at multiple sites.

Despite these limitations, our study has many strengths. First, while treatment decisions have previously been dichotomized into “acceptance” or “refusal,” we found evidence for a spectrum of decision-making, and were able to interview participants in each category. In addition, the explanatory model that emerged from our qualitative research has several important implications for the public health strategies now being explored in areas of sub-Saharan Africa with high-HIV prevalence rates (e.g., universal voluntary testing with an immediate “test-and-treat” strategy [52, 53]) by providing a framework for understanding how and when people may delay starting treatment, despite optimal access to care. Finally, our results revealed several modifiable factors that could be targeted in future interventions to increase ART initiation, including: economic incentives, peer-based social support programs, and further education about the side-effects of ARTs currently available in South Africa.

Conclusion

Optimizing engagement and long-term retention of adults living with HIV requires understanding decision-making in the pre-ART period. This qualitative study in Soweto, South Africa, provides a novel explanatory model of treatment refusal, which recognizes the relative importance of perceived risks associated with starting treatment in otherwise asymptomatic adults. These risks relate to the social costs incurred when disclosing one’s status in a community where being identified as “sick” from HIV may potentially be the tipping point in a life that may hang in a fragile balance. Conversely, social integration and connectivity may provide those who test positive with sufficient support to promote effective coping strategies and overcome fears related to treatment initiation. Future research should test interventions that target modifiable factors identified through this study to optimize engagement in care.

References

The gap report [Internet]. UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf (2014). Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

Katz IT, Bassett IV, Wright AA. PEPFAR in transition—implications for HIV care in South Africa. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1385–7.

Department of State: The Office of Electronic Information B of PA. Treatment: direct FY2013 antiretroviral treatment results [Internet]. http://www.pepfar.gov/press/222831.htm (2014). Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: South Africa operational plan report FY 2012 [Internet]. http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/212156.pdf (2013). Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey [Internet]. Human Sciences Research Council Press; 2014. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/4565/SABSSM%20IV%20LEO%20final.pdf. Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

Kranzer K, Zeinecker J, Ginsberg P, Orrell C, Kalawe NN, Lawn SD, et al. Linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e13801.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global report UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic: 2012 [Internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf. Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

Patten GE, Cox V, Stinson K, Boulle AM, Wilkinson LS. Advanced HIV disease at antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation despite implementation of expanded ART eligibility guidelines during 2007–2012 in Khayelitsha, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2014;59:456–7.

Smith LR, Amico KR, Shuper PA, Christie S, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, et al. Information, motivation, and behavioral skills for early pre-ART engagement in HIV care among patients entering clinical care in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2013;25:1485–90.

Bassett IV, Regan S, Chetty S, Giddy J, Uhler LM, Holst H, et al. Who starts antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa?… not everyone who should. AIDS Lond Engl. 2010;24(Suppl 1):S37–44.

Curran K, Ngure K, Shell-Duncan B, Vusha S, Mugo NR, Heffron R, et al. “If I am given antiretrovirals I will think I am nearing the grave”: Kenyan HIV serodiscordant couples’ attitudes regarding early initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Lond Engl. 2014;28:227–33.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505.

Anglemyer A, Rutherford GW, Horvath T, Baggaley RC, Egger M, Siegfried N. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009153.

Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell M-L. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339:966–71.

Cloete C, Regan S, Giddy J, Govender T, Erlwanger A, Gaynes MR, et al. The linkage outcomes of a large-scale, rapid transfer of HIV-infected patients from hospital-based to community-based clinics in South Africa. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1:ofu058.

Katz IT, Essien T, Marinda ET, Gray GE, Bangsberg DR, Martinson NA, et al. Antiretroviral refusal among newly diagnosed HIV-infected adults in Soweto, South Africa. AIDS Lond Engl. 2011;25:2177–81.

Heffron R, Ngure K, Mugo N, Celum C, Kurth A, Curran K, et al. Willingness of Kenyan HIV-1 serodiscordant couples to use antiretroviral-based HIV-1 prevention strategies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:116–9.

Mujugira A, Celum C, Thomas KK, Farquhar C, Mugo N, Katabira E, et al. Delay of antiretroviral therapy initiation is common in East African HIV-infected individuals in serodiscordant partnerships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:436–42.

Nachega JB, Uthman OA, del Rio C, Mugavero MJ, Rees H, Mills EJ. Addressing the Achilles’ heel in the HIV care continuum for the success of a test-and-treat strategy to achieve an AIDS-free generation. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:S21–7.

Geng EH, Bwana MB, Muyindike W, Glidden DV, Bangsberg DR, Neilands TB, et al. Failure to initiate antiretroviral therapy, loss to follow-up and mortality among HIV-infected patients during the pre-ART period in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:e64–71.

Stinson K, Myer L. Barriers to initiating antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy: a qualitative study of women attending services in Cape Town, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2012;11:65–73.

Anon. Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital website [Internet]. http://www.chrishanibaragwanathhospital.co.za. Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

Meintjes G, Maartens G, Boulle A, Conradie F, Goemaere E. South African treatment guidelines. S Afr J HIV Med. 2012;13:114–33.

Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1997.

Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001056.

Strauss AC, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: second edition: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1998.

Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–31.

Finucane ML, Alhakami A, Slovic P, Johnson SM. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J Behav Decis Mak. 2000;13:1–17.

Kahn TR, Desmond M, Rao D, Marx GE, Guthrie BL, Bosire R, et al. Delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-discordant couples in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2013;25:265–72.

Unge C, Johansson A, Zachariah R, Some D, Van Engelgem I, Ekstrom AM. Reasons for unsatisfactory acceptance of antiretroviral treatment in the urban Kibera slum, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2008;20:146–9.

Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR. The importance of social ties in sustaining medication adherence in resource-limited settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1391–3.

Bangsberg DR, Deeks SG. Spending more to save more: interventions to promote adherence. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:54–6; W-13.

Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, Biraro IA, Wyatt MA, Agbaji O, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000011.

Weiser SD, Tuller DM, Frongillo EA, Senkungu J, Mukiibi N, Bangsberg DR. Food insecurity as a barrier to sustained antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10340.

Tuller DM, Bangsberg DR, Senkungu J, Ware NC, Emenyonu N, Weiser SD. Transportation costs impede sustained adherence and access to HAART in a clinic population in southwestern Uganda: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:778–84.

Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Emenyonu N, Senkungu JK, Martin JN, Weiser SD. The social context of food insecurity among persons living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2011(73):1717–24.

Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Tugenberg T. Social relationships, stigma and adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18:904–10.

Samuels FA, Rutenberg N. “Health regains but livelihoods lag”: findings from a study with people on ART in Zambia and Kenya. AIDS Care. 2011;23:748–54.

Izugbara CO, Wekesa E. Beliefs and practices about antiretroviral medication: a study of poor urban Kenyans living with HIV/AIDS. Sociol Health Illn. 2011;33:869–83.

Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16 [Internet]. http://www.jiasociety.org/index.php/jias/article/view/18640. Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

MacPherson P, MacPherson EE, Mwale D, Squire SB, Makombe SD, Corbett EL, et al. Barriers and facilitators to linkage to ART in primary care: a qualitative study of patients and providers in Blantyre, Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15 [Internet]. http://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.bu.edu/pmc/articles/PMC3535694/. Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, Toefy Y, Cain D, Cherry C, et al. Development of a brief scale to measure AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:135–43.

Wolfe WRW, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Thior I, Makhema JM, Dickinson DB, Mompati KF, Marlink RG. Effects of HIV-related stigma among an early sample of patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Botswana. AIDS Care. 2006;18:931–3.

Roura M, Urassa M, Busza J, Mbata D, Wringe A, Zaba B. Scaling up stigma? The effects of antiretroviral roll-out on stigma and HIV testing. Early evidence from rural Tanzania. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:308–12.

Mansergh G, Marks G, Simoni JM. Self-disclosure of HIV infection among men who vary in time since seropositive diagnosis and symptomatic status. AIDS Lond Engl. 1995;9:639–44.

Hays RB, McKusick L, Pollack L, Hilliard R, Hoff C, Coates TJ. Disclosing HIV seropositivity to significant others. AIDS Lond Engl. 1993;7:425–31.

Patel R, Ratner J, Gore-Felton C, Kadzirange G, Woelk G, Katzenstein D. HIV disclosure patterns, predictors, and psychosocial correlates among HIV positive women in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2012;24:358–68.

Alonzo AA, Reynolds NR. Stigma, HIV and AIDS: an exploration and elaboration of a stigma trajectory. Soc Sci Med. 1982;1995(41):303–15.

Nam SL, Fielding K, Avalos A, Dickinson D, Gaolathe T, Geissler PW. The relationship of acceptance or denial of HIV-status to antiretroviral adherence among adult HIV patients in urban Botswana. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2008(67):301–10.

Green HD, Atuyambe L, Ssali S, Ryan GW, Wagner GJ. Social networks of PLHA in Uganda: implications for mobilizing PLHA as agents for prevention. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:992–1002.

Guthrie BL, Choi RY, Liu AY, Mackelprang RD, Rositch AF, Bosire R, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral initiation in HIV-1-discordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2011(58):e87–93.

Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57.

Hayes R, Ayles H, Beyers N, Sabapathy K, Floyd S, Shanaube K, et al. HPTN 071 (PopART): rationale and design of a cluster-randomised trial of the population impact of an HIV combination prevention intervention including universal testing and treatment—a study protocol for a cluster randomised trial. Trials. 2014;15:57.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible with funding from U.S. National Institutes of Health 5 K23MH09766703, and help from the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI060354), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NIDDK, NIGMS, FIC, and OAR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

No authors have any competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Katz, I.T., Dietrich, J., Tshabalala, G. et al. Understanding Treatment Refusal Among Adults Presenting for HIV-Testing in Soweto, South Africa: A Qualitative Study. AIDS Behav 19, 704–714 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0920-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0920-y