Abstract

Alcohol consumption is associated with risks for sexually transmitted infections (STI), including HIV/AIDS. In this paper, we systematically review the literature on alcohol use and sexual risk behavior in southern Africa, the region of the world with the greatest HIV/AIDS burden. Studies show a consistent association between alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV infection. Among people who drink, greater quantities of alcohol consumption predict greater sexual risks than does frequency of drinking. In addition, there are clear gender differences in alcohol use and sexual risks; men are more likely to drink and engage in higher risk behavior whereas women's risks are often associated with their male sex partners' drinking. Factors that are most closely related to alcohol and sexual risks include drinking venues and alcohol serving establishments, sexual coercion, and poverty. Research conducted in southern Africa therefore confirms an association between alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV. Sexual risk reduction interventions are needed for men and women who drink and interventions should be targeted to alcohol serving establishments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol is the most commonly used psychoactive substance and alcohol is among the most prevalent behaviors associated with sexual risks for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI). Research conducted since the middle 1980s has repeatedly shown that alcohol use is related to sexual risks in several populations, especially among those with the highest rates of HIV infections (Weinhardt & Carey, 2001). Alcohol elevates sexual risks through multiple channels, including risk-taking personality characteristics, drinking environments, expectations regarding the effects of alcohol on risk-taking and the psychogenic effects of alcohol on decision making (Cook & Clark, 2005). The association between drinking and sexual risk behaviors has lead to interventions that address alcohol use for sexual risk reduction (Palepu et al., 2005) and there are HIV prevention interventions that specifically target people who drink (Kelly et al., 1991, 1992).

Model of alcohol use and sexual risk behavior, adapted from Morojele et al. (2006)

Among the more than 40 million people in the world who are infected with HIV, two out of three live in sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS, 2006). Coinciding with the world's greatest HIV/AIDS burden, southern Africa also consumes great quantities of alcohol. Alcohol use has a long history in southern Africa, dating back hundreds of years and spanning social, cultural, and economic spectrums (Nielsen et al., 1989). In the Republic of South Africa, for example, individuals who drink consume an average of 20 liters of alcohol per year, representing one of the highest volumes of per capita alcohol consumption in the world (Parry, 2005). Forty percent of South African men and 15% of women drink alcohol, with significant numbers drinking heavily (Shisana et al., 2005). There is also evidence that alcohol consumption in southern Africa is increasing over time (Parry et al., 2004).

Like elsewhere in the world, alcohol use is often associated with sexual risks in southern Africa.Footnote 1 However, unlike anywhere else, the implications of alcohol use on risks for HIV infection are greatest in southern Africa because HIV prevalence rates are highest. This article reviews the current state of knowledge on the association between alcohol use and HIV risk behavior in southern Africa. To guide our review, we have adopted a conceptual model of the association between alcohol use and sexual risks (Morojele et al., 2006, described below). We also critically review the methodological issues that should be considered when interpreting results in the existing literature. Finally, we conclude by discussing the implications of the major study findings for future research and developing HIV prevention interventions in southern Africa.

Alcohol and risks for HIV infection in Southern Africa

Our literature review was performed using a combination of automated and manual search strategies. We searched PubMed and PsycInfo data bases for all journal dating back to 1985 using the key terms `Africa, alcohol, HIV, AIDS, risk behavior.' We also conducted manual searches of articles cited in reference sections of papers identified through automated search. In all, we located 84 articles. Using the criteria that studies had to have measured both alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV in the same timeframe and analyzed their associations, we retained 33 empirical papers. Table 1 presents a brief summary of findings and methodologies for the studies included in this review.

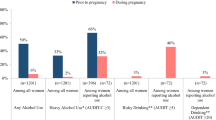

We structured our review in accordance with a conceptual model designed to explain alcohol-sexual risk associations in Africa (Morojele et al., 2006). The model includes factors that are common to biopsychosocial models of alcohol use and has been framed with direct relevance to alcohol use in southern Africa. As shown in Fig. 1, predictors of alcohol use, such as socio-cultural, community, and intrapersonal factors influence alcohol consumption which in turn has direct psychoactive effects. Alcohol therefore influences sexual risk behavior through its effects on cognitive processes (e.g., reasoning ability, judgment, and sense of responsibility). This framework also recognizes an array of factors that can moderate the effects of alcohol on sexual risk behavior, such as drinking environments, economic conditions, and sexual coercion. Morojele et al.'s conceptual model, therefore, provides a comprehensive framework for organizing empirical research on the association between alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS. Although this model overlaps with past models of alcohol use, it is important to note that Morojele et al. (2006) constructed this model focusing on factors that are most relevant to African societies. Our review of the research literature therefore follows this framework for understanding the association between alcohol use and sexual risks in southern Africa.

Alcohol use and sexual risks

As many as 50% of people living in areas of southern Africa where HIV is most prevalent report current alcohol use (Shisana et al., 2005). Alcohol use is associated with STI and HIV prevalence. Studies in southern Africa have shown that testing positive for STIs (e.g., Gwati, Guli, & Todd, 1995; Shaffer, Njeri, Justice, Odero, & Tierney, 2004) and HIV (e.g., Ayisi et al., 2000; Shisana et al., 2005) are independently associated with alcohol use. Men are more likely to drink than women, but women are more likely to drink with their sex partners than are men (Morojele et al., 2004). For example, only 1% of HIV positive women themselves reported drinking before sex in their current relationship, but 19% reported that their current sex partner usually drinks before sex (Mataure et al., 2002). Although men are more likely to drink frequently than women, women drink in greater quantities. These gender differences in alcohol use illustrate one of several ways in which women's risks for HIV are attributable to men's behavior.

Populations that are at greatest risk for HIV/AIDS in southern Africa also have the greatest history of alcohol use. For example, among drug using commercial sex workers, 26% report that alcohol was the first drug they ever used, 51% had started drinking by age 17, and 18% drank daily (Wechsberg, 2005). Sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic patients who are also at high risk for HIV commonly report drinking before sex (Simbayi et al., 2004a). Alcohol use is also associated with testing positive for an STI among women employed in Kenyan plantations (Feldblum et al., 2000), and daily alcohol use predicts incident STI diagnoses among Kenyan commercial sex workers (Yadav et al., 2005).

Although frequency of drinking is related to increased sexual risks, the number of times individuals drink appears less important in predicting sexual risks than does the quantity of alcohol consumed. Campbell et al. (2002) and Campbell (2003), for example, found that men and women who drink are significantly more likely to be HIV positive, but frequency of drinking was unrelated to HIV status. Morojele et al. (2004) also found that frequency of alcohol use was not associated with sexual risk behaviors, but quantity of alcohol consumed was related to having greater numbers of recent sex partners. People who drink more heavily and report being intoxicated in sexual situations also report less condom use and more concurrent sex partners, clearly demonstrating higher risk for HIV (Dunkle et al., 2004; Mataure et al., 2002; Mnyika, Klepp, Kvale, & Ole-King'ori, 1997; Zachariah et al., 2003).

In summary, people who drink alcohol in southern Africa are at higher risk for HIV than individuals who do not drink. The association between drinking and sexual risks is also observed across a wide array of populations. Any alcohol use at all and drinking greater quantities of alcohol are closely associated with HIV transmission risks in southern Africa.

Predictors of alcohol use

Following our conceptual framework presented in Fig. 1, several factors likely predict alcohol use in sexual contexts, including community norms, and intrapersonal characteristics. Unfortunately, relatively few studies have examined factors that predict alcohol use and sexual risks in Africa. Although people who drink often recognize the potential for alcohol to impair their judgment and therefore increase their risks for STI/HIV, this awareness does not necessarily translate to increased perceptions of personal risks for STI and HIV among drinkers (Lewis et al., 2005). Studies in southern Africa suggest that cognitive and personality factors are associated with alcohol-related sexual risks. Consistent with the gender differences in alcohol use discussed above, men are significantly more likely to expect that alcohol will increase their sexual desires, whereas women expect the opposite effects of alcohol on sexual desires. In addition, sexual enhancement expectations are related to greater numbers of sex partners and the number of times people regret having had sex (Morojele et al., 2004).

The most widely studied personality disposition related to both alcohol use and sexual risk behavior is sensation seeking (Hoyle, Fejfar, & Miller, 2000). Sensation seeking is defined as the propensity to seek optimal sensations through novel and arousing experiencing. The sensation seeking personality disposition reliably predicts engaging in an array of risk behaviors including sexual behaviors and alcohol use across cultures (Zuckerman, 1994). Kalichman et al. (2006) reported that sensation seeking predicts both alcohol use in sexual contexts and a cumulative index of HIV transmission risk factors among STI clinic patients in South Africa. The potential importance of underlying personality characteristics in predicting alcohol use and risk behavior is further supported by research that shows alcohol use is only one of several behaviors that cluster together to increase risk for HIV transmission (Bailey, Neema, & Othieno, 1999). Drinking alcohol as a means of coping with stress is also related to engaging in higher risk behaviors for HIV transmission (Jones, Ross, Weiss, Bhat, & Chitalu, 2005; Wechsberg, Luseno, & Lam, 2005). Lifestyles that are characterized by alcohol use, especially heavy drinking, can therefore compound HIV risk through multiple channels (Morojele et al., 2004).

Psychoactive effects of alcohol

Few studies have examined alcohol's direct effects on thoughts and behaviors in relation to sexual risks in Africa. One qualitative study conducted with STI clinic patients found that alcohol use to the point of intoxication was believed to lower sexual inhibitions and created barriers to using condoms among both men and women (Simbayi, Mwaba, & Kalichman, 2006). This finding is consistent with studies that report that greater quantities of alcohol consumption are associated with engaging in unprotected sex as well as other risk behaviors in southern Africa (Wechsberg et al., 2005). Unfortunately, no research conducted in Africa has yet investigated the actual psychoactive effects of alcohol and related mechanisms on subsequent risks for HIV transmission.

Moderating factors

In our conceptual model, moderating factors are the forces that influence the use of alcohol and its relationship to HIV risks, including environmental factors, economics, and sexual coercion (Morojele et al., 2006).

Drinking environments

Businesses and venues that serve alcohol are often the very places that link alcohol use with risk for HIV infection. Informal alcohol serving establishments, such as private homes where alcoholic beverages are sold and served, are also often the same places where sex partners meet (Morojele et al., 2004). Research conducted in South Africa has demonstrated the close association between patronizing shebeens and HIV risks. Weir et al. (2003) mapped the linkages among places where people meet new sex partners and places where people drink alcohol. The study demonstrated a remarkable overlap among these venues; over 85% of the locations where people meet sex partners are alcohol serving establishments. The overlap was observed in both urban and rural areas. Across three cities, between 78% and 87% of new sex partners were met at shebeens. As many as 57% of men and 46% of women who drink at shebeens report having two or more sex partners in the past two weeks. Unfortunately, shebeens and other alcohol serving establishments, such as taverns and bottle stores, rarely have condoms available for their customers (Weir et al., 2003).

In Ugandan villages, 4% of people live in homes that sell alcohol but 15% of people living in these homes are HIV positive, nearly double HIV prevalence in the surrounding community (Mbulaiteye et al., 2000). HIV risks are notably higher for people who go to nightclubs, bottle stores, and taverns (Lewis et al., 2005; Mataure et al., 2002). The most studied drinking places in relation to HIV risks in Africa are beer halls; large social venues that primarily serve beer. HIV prevalence is as much as two times higher among men in Zimbabwe who attend beer halls than among men in the general Zimbabwe population (Bassett et al., 1996). Sixty percent of men and 41% of women who report having multiple current sex partners drink at beer halls (Lewis et al., 2005). Fritz et al. (2002) demonstrated that HIV prevalence increases with greater use of alcohol in beer halls. The number of days of the week that men drink correlates with their frequency of engaging in unprotected sex with casual partners.

In addition to their patrons, employees of alcohol serving establishments demonstrate considerable risks for HIV infection. Kapiga et al. (2003) reported that men who work in Tanzanian bars and hotels and drink at least once a week were significantly more likely to have Herpes Simplex Virus, a known marker for HIV transmission, than their male co-workers who did not drink. Similarly, women who work in food and recreational businesses near gold mines and drink are significantly more likely to have HIV and other STI than other women who drink in the communities that surround the mines but do not work in food and recreation businesses (Clift et al., 2003).

The connection between alcohol serving establishments and sexual risks for HIV is at least in part a function of drinking in sexual networking contexts. Drinking before sex is more common with non-regular than with regular sex partners (Myer, Matthews, & Little, 2002). Drinking establishments may amplify HIV transmission risks by providing a place where high-risk sex encounters can easily unfold (Fritz et al., 2002). Alcohol establishments are often themselves sex venues, where back rooms, back corners, and adjacent buildings or shacks offer locations for sex (Morojele et al., 2006). Places that serve alcohol therefore appear uniquely linked to HIV transmission risks in southern Africa.

Economic conditions

Both HIV infection and alcohol use are most concentrated in areas of poverty. Although poverty may well be the foundation for the association between alcohol use and HIV risks in southern Africa, there is surprisingly little research on the connection between poverty, alcohol use, and HIV infection in this region. One factor that connects poverty to alcohol and HIV risk is transactional sex (e.g., exchanging sex for money or to meet survival needs). Poverty and unemployment foster both substance use and commercial sex work. In fact, transactional sex in Africa is directly related to alcohol use (Dunkle et al., 2004). For example, among women who meet sex partners in shebeens and taverns, nearly half say that their sex partners buy them drinks for sex. The exchange of alcohol or gifts for sex is most common between older men and younger women (Mataure et al., 2002). Women who are involved in sexual exchange are at greatest risk when they work in bars or nightclubs as compared to women who exchange sex in homes (Yadav et al., 2005).

The pressures of living in poverty are related to drinking and risks for HIV infection beyond the risks associated with transactional sex. Research conducted in three urban communities in Cape Town, for example, found that sexual risk behaviors were related to perceived stress of poverty (Kalichman et al., 2006). Individuals who perceived greater stress resulting from violence, crime, and discrimination reported greater risks for HIV infection. In this study, alcohol use was related to both perceived stress and HIV risk behavior. Importantly, alcohol use did not account for the association between perceptions of poverty-related social problems and HIV risk behaviors. Perceptions of poverty and alcohol use are therefore related to each other and both are associated with HIV risk behaviors.

Sexual coercion

Sexual assault is prevalent in southern Africa and sexual violence is related to alcohol use and HIV transmission risks (Dunkle et al., 2004; Jewkes, Levin, & Penn-Kekana, 2002). Men who have a history of sexual violence are more likely to drink than men who have not been sexually assaultive (Abrahams, Jewkes, Hoffman, & Laubsher, 2004). Likewise, alcohol use is associated with having been sexually assaulted among women (King et al., 2004). In Uganda, for example, half of women who had been abused reported that their partner drank and one in four reported that their partner drank frequently (Koenig et al., 2003). The association between relationship violence and HIV risk is at least partly accounted for by alcohol use (Phorano, Nthomang, & Ntseane, 2005). Although it is clear that alcohol consumption and sexual violence are related, their temporal association is less clear. That is alcohol use may precede or follow sexual violence. The power dynamics between men and women are known to foster HIV risk behaviors in southern Africa and alcohol can be used as an instrument for leveraging power in these relationships.

Methodological considerations

Table 1 describes the measures and samples reported in studies of alcohol use in relation to sexual risk behavior in southern Africa. This literature is composed mostly of cross-sectional studies that have relied on self-reported alcohol use and sexual behavior. Findings are therefore constrained in terms of their ability to draw causal conclusions and all reports of behavior in this literature must be interpreted with caution. What the literature is most seriously missing are longitudinally designed studies between alcohol use and sexual risks. Only with prospective research can the temporal associations between alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors be disentangled. For example, ecological momentary assessments can record drinking and sexual behavior on a daily basis, as well as mediating factors such as mood, stress, and relationship events. Timeline follow-back assessment procedures can similarly determine the temporal sequence and causal links of alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors.

The research in this area is also limited by sampling constraints. Although some studies have used large samples drawn from general populations, most studies have relied on small convenience samples, particularly of individuals recruited from alcohol serving establishments. In some cases, survey venues were selected explicitly because they serve alcohol and are known as locations where sexual partners meet, such as taverns, beer halls, and informal drinking establishments. Studies have typically included questions about drinking within a more comprehensive behavioral survey that also included questions about sexual risk behavior.

Studies of alcohol use and sexual risk behavior have also varied in their strategies for measuring drinking and its relationship to sexual risk. Measures of alcohol use have included global retrospective accounts without attention to frequency or quantity of alcohol use; i.e., any use of alcohol in the past or any current use of alcohol. In contrast to measures of global alcohol use, event level analyses afford a greater degree of precision in estimating alcohol use in relation to sexual behavior (Weinhardt & Carey, 2001). Unfortunately, few studies have assessed alcohol at the event level and have therefore been unable to examine drinking in proximity to sexual risk behaviors. In one exceptional study that could be considered a model for event level analysis, Myer et al. (2002) investigated over 3,200 sexual events reported by 384 individuals, allowing for a direct examination of condom use during sexual episodes which did and did not involve alcohol over the course of a two-week period. This study therefore directly tested the hypothesis as to whether sexual risks co-occur with alcohol use.

Some studies we reviewed asked participants to report whether they had drank at all in a specified time period. Studies also examined substance use by collapsing alcohol use with the use of any other drugs (Dunkle et al., 2004). Studies have also defined drinking as a lifestyle characteristic (e.g., Hargreave et al., 2002). It is often not possible to differentiate alcohol use from alcohol abuse and dependence although the distinction is important in understanding HIV risks. Similar problems are common in measuring of sexual risk behavior in this literature. Some studies in our review defined sexual behavior in equally vague terms, such as ``having ever had a relationship'' (e.g., Mugisha & Zulu, 2004). More recent research has included measures of alcohol use in sexual contexts and there are increasing numbers of studies that include brief, standardized tests of alcohol use and misuse, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT, Saunders, Aasland, Babor, DeLaFuente, & Gran,t, 1993). These studies offer greater precision in describing alcohol use as well as its association to sexual risks.

Implications for future research

Most of the research available in the current literature included measures of alcohol and sexual risk behavior as part of studies that were not focused on their association. Thus, most study findings are based on a few imprecise measures of alcohol and sexual risks. There is a great need for research that uses well defined and standard measures of alcohol and sexual risk behavior to confirm and refine the observed associations. At minimum, alcohol measures must distinguish between alcohol use, alcohol abuse, and alcohol dependence and sexual behavior, all assessed within the same time frame. Research is also needed to examine alcohol use in relation to sexual behavior using prospective study designs as well as research conducted at the event level, the two types of studies that are most effective at disentangling confounding factors from the alcohol and sexual behavior association.

The mechanisms that account for the associations between alcohol and risks have not been widely studied in southern Africa. Factors such as personality dispositions, alcohol expectancies, sexual coercion and the connection between drinking and poverty warrant further study. Future research is most urgently needed to test the efficacy of interventions designed to reduce HIV risks, particularly risk-related alcohol use among populations at greatest risk for HIV infection. There is a particular need for interventions that target alcohol use as a risk factor for HIV transmission. Interventions should also be tested that target men and women who drink, especially those who frequent alcohol serving establishments.

Implications for HIV prevention interventions

The direct and indirect effects of alcohol on sexual risk behavior offer multiple opportunities for HIV prevention. Interventions can be designed to reduce alcohol use in relation to sexual behavior as well as target predictors and moderators of the association between alcohol use and sexual risks.

At the individual level, HIV prevention and alcohol reduction interventions can be integrated into existing counseling services, such as counseling for HIV risk reduction in clinic settings, HIV counseling and testing services, and substance abuse treatment. Brief prevention counseling models for HIV risk reduction have demonstrated positive effects in southern Africa and could be adapted to integrate brief education and counseling for reducing risks associated with alcohol use (Allen et al., 1992; Simbayi et al., 2004b). One approach to brief alcohol treatment that can feasibly be integrated with brief HIV risk reduction counseling is the World Health Organization's brief alcohol counseling model (Babor et al., 1992). This model uses the AUDIT to define levels of alcohol risk and tailors alcohol reduction counseling to these levels. Brief integrated HIV risk reduction and alcohol treatment counseling may be a viable strategy for targeting particularly high risk populations, such as persons undergoing HIV counseling and testing, women in antenatal clinics, and STI clinic patients.

Social level interventions can target families, schools, churches and other social and cultural institutions. Families have become a common target for both substance abuse prevention and HIV prevention interventions and these approaches have started to be adapted for use in southern Africa. For example, the Collaborative HIV/AIDS and Adolescent Mental Health Program (CHAMP) has been adapted for use in South Africa (Bhana et al., 2003). In this model, youth, their families, schools and other elements of the community are targeted for reducing sexual risks by increasing knowledge, enhancing motivations, and building risk reduction skills. This model is already being tested in South Africa and provides an opportunity for addressing alcohol-related HIV risks (Bhana et al., 2003).

At the structural level, HIV prevention interventions can be implemented in alcohol serving establishments. By integrating HIV prevention into well-established and frequently attended social institutions, such as beer halls, shebeens, and taverns HIV prevention activities have the potential to reach large numbers of persons at greatest risk for HIV infection. Fritz et al. (2002) reported that beer hall owners express interest in the possibility of implementing HIV prevention interventions in their businesses, suggesting that there is an opportunity for HIV prevention interventions to be delivered in alcohol serving businesses. Condoms can be made accessible in drinking establishments with minimal disruption to the environment and can be promoted with simple messages displayed in small media such as posters or brochures. More intensive intervention models, such as Kelly et al.'s (1991, 1992) Popular Opinion Leader (POL) intervention demonstrated positive effects when delivered to gay and bisexual men attending bars in US cities. These models are particularly compelling for alcohol serving establishments because of the overlap between social and sexual networks that develop in these settings. Culturally adapted multi-level alcohol – HIV risk reduction interventions for use in southern Africa should remain a top public health priority.

Notes

We collectively include Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, which are East African countries, along with southern African countries as southern Africa throughout.

References

Abrahams, N., Jewkes, R., Hoffman, M., & Laubsher, R. (2004). Sexual violence against intimate partners in Cape Town: Prevalence and risk factors reported by men. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82, 330–337.

Allen, S., Tice, J., Van de Perre, P., Serufilira, A., Hudes, E., Nsengumuremyi, F. (1992). Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. British Medical Journal, 304, 1605–1609.

Ayisi, J. G., van Eijk, A. M., ter Kuile, F. O., Kolczak, M. S., Otieno, J. A., Misore, A. O. (2000). Risk factors for HIV infection among asymptomatic pregnant women attending an antenatal clinic in western Kenya. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 11, 393–401.

Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R., Saunders, J., & Grant, M. (1992). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva: World Health Care Organization.

Bailey, R. C., Neema, S., & Othieno, R. (1999). Sexual behaviors and other HIV risk factors in circumcised and uncircumcised men in Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 22, 294–301.

Bhana, A., Petersen, I., Mason, A., Mahintsho, Z., Bell, C. C., McKay, M. (2003). Adaptation of the CHAMP manual for South Africa. Poster presented at NIMH Family Conference, July 27–30, 2003, Washington DC, USA.

Campbell, C., Williams, B., & Gilgen, D. (2002). Is social capital a useful conceptual tool for community level influences on HIV infection? An exploratory case study from South Africa. AIDS Care, 14, 41–54.

Campbell, E. K. (2003). A note on alcohol consumption and sexual behaviour of youths in Botswana. African Sociological Review, 7, 146–161.

Chikwem, J. O., Ola, T. O., Gashau, W., Chikwem, S. D., Bajami, M., & Mambula, S. (1988). Impact of health education on prostitutes' awareness and attitudes to Acquire Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Public Health, 102, 439–445.

Clift, S., Anemona, A., Watson-Jones, D., Kanga, L., Ndeki, L., & Changalucha, J. (2003). Variations of HIV and STI prevalences within communities neighbouring new goldmines in Tanzania: Importance for intervention design. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 79, 307–312.

Cook, R. L. & Clark, D. (2005). Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 32, 156–164.

Dunkle, K. L., Jewkes, R. K., Brown, H. C., Gray, G. E., McIntryre, J. A., & Harlow, S. D. (2004). Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: Prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 1581–1592.

Feldblum, P. J., Kuyoh, M., Omari, M., Ryan, K. A., Bwayo, J. J., & Welsh, M. (2000). Baseline STD prevalence in a community intervention trial of the female condom in Kenya. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 76, 454–456.

Fritz, K. E., Woelk, G. B., Bassett, M. T., McFarland, W. C., Routh, J. A., & Tobaiwa, O. (2002). The association between alcohol use, sexual risk behavior, and HIV infection among men attending beer halls in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior, 6, 221–228.

Gwati, B., Guli, A., & Todd, C. H. (1995). Risk factors for sexually transmitted disease amongst men in Harare, Zimbabwe. Central African Journal of Medicine, 41, 179–181.

Hargreaves, J. R., Morison, L. A., Chege, J., Rutenburg, N., Kahindo, M., & Weiss, H. A. (2002). Socioeconomic status and risk of HIV infection in an urban population in Kenya. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 7, 793–802.

Hoyle, R., Fejfar, M., & Miller, J. (2000). Personality and sexual risk taking: A quantitative review. Journal of Personality, 68, 1203–1231.

Jewkes, R., Levin, J., & Penn-Kekana, L. (2002). Risk factors for domestic violence: Findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 1603–1617.

Jones, D. L., Ross, D., Weiss, S. M., Bhat, G., & Chitalu, N. (2005). Influence of partner participation on sexual risk behavior reduction among HIV-positive Zambian women. Journal of Urban Health, 82, iv92–iv100.

Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Jooste, S., Cain, D., & Cherry, C. (In press). Sensation Seeking, Alcohol Use, and Sexual Behaviors among Sexually Transmitted Infection Clinic Patients, Cape Town, South Africa. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors.

Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Kagee, A., Toefy, Y., Cain, D., & Cherry. C (2006). Association of poverty, substance use, and HIV transmission risk behaviors in three South African communities. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 1641–1649.

Kapiga, S. H., Lyamuya, E. F., Lwihula, G. K., & Hunter, D. J. (1998). The incidence of HIV infection among women using family planning methods in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS, 12, 75–84.

Kapiga, S. H., Sam, N. E., Shao, J. F., Masenga, E. J., Renjifo, B., & Kiwelu, I. E. (2003). Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 infection among female bar and hotel workers in northern Tanzania: Prevalence and risk factors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 30, 187–192.

Kapiga, S. H., Sam, N. E., Shao, J. F., Renjifo, B., Masenga, E. J., & Kiwelu, I. E. (2002). HIV-1 epidemic among female bar and hotel workers in northern Tanzania: Risk factors and opportunities for prevention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 29, 409–417.

Kelly, J. A., St. Lawrence, J., Stevenson, Y., Hauth, A., Kalichman, S., & Diaz, Y. (1992). Community AIDS/HIV risk reduction: The effects of endorsements by popular people in three cities. American Journal of Public Health, 82, 1483–1489.

Kelly, J. A., St. Lawrence, J., Diaz, Y., Stevenson, Y., Hauth, A., & Brasfield, T., (1991). HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of a population: An experimental community-level analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 81, 168–171.

King, G., Flisher, A. J., Noubary, F., Reece, R., Marais, A., & Lombard, C. (2004). Substance abuse and behavioral correlates of sexual assault among South African adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 683–696.

Koenig, M. A., Lutalo, T., Zhao, F., Nalugoda, F., Kiwanuka, N., & Wabwire-Mangen, F. (2004). Coercive sex in rural Uganda: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Social Science and Medicine, 58, 787–798.

Koenig, M. A., Lutalo, T., Zhao, F., Nalugoda, F., Wabwire-Mangen, F., & Kiwanuka, N. (2003). Domestic violence in rural Uganda: Evidence from a community-based study. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 81, 53–60.

Lewis, J. J. C., Garnett, G. P., Mhlanga, S., Nyamukapa, C. A., Donnelly, C. A., & Gregson, S. (2005). Beer halls as a focus for HIV prevention activities in rural Zimbabwe. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 32, 364–369.

Mbulaiteye, S. M., Ruberantwari, A., Nakiyingi, J. S., Carpenter, L. M., Kamali, A., & Whitworth, J. A. G. (2000). Alcohol and HIV: A study among sexually active adults in rural southwest Uganda. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29, 911–915.

Mnyika, K. S., Klepp, K. I., Kvale, G., & Ole-King'ori, N. (1997). Determinants of high-risk sexual behaviour and condom use among adults in the Arusha region, Tanzania. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 8, 176–183.

Morojele, N. K., Kachieng'a, M. A., Nkoko, M. A., Moshia, A. M., Mokoko, E., & Parry, C. D. H. (2004). Perceived effects of alcohol use on sexual encounters among adults in South Africa. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies, 3, 1–20.

Morojele, N. K., Kachieng'a, M. A., Mokoko, E., Nkoko, M. A., Parry, C. D. H., & Nkowane, A. M. (2006). Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 217–227.

Morrison, C. S., Sunkutu, M. R., Musaba, E., & Glover, L. H. (1997). Sexually transmitted disease among married Zambian women: The role of male and female sexual behaviour in prevention and management. Genitourinary Medicine, 73, 555–557.

Mugisha, F., & Zulu, E. M. (2004). The influence of alcohol, drugs and substance abuse on sexual relationships and perception of risk to HIV infection among adolescents in the informal settlements of Nairobi. Journal of Youth Studies, 7, 279–293.

Myer, L., Matthews, C., & Little, F. (2002). Condom use and sexual behaviors among individuals procuring free male condoms in South Africa: A prospective study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 29, 239–241.

Palepu, A., Raj, A., Horton, N., Tibbetts, N., Meli, S., & Samet, J. (2005). Substance abuse treatment and risk behaviors among HIV infected persons with alcohol problems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25, 3–9.

Parry, C. D. (2005). South Africa: Alcohol today. Addictions, 100, 426–429

Parry, C. D., Myers, B., Morojele, N. K., Flisher, A. J., Bhana, A., & Donson, H. (2004). Trends in adolescent alcohol and other drug use: Findings from three sentinel sites in South Afria (1997–2001). Journal of Adolescence, 27, 429–440.

Phorano, O. D., Nthomang, K., & Ntseane, D. (2005). Alcohol abuse, gender-based violence and HIV/AIDS in Botswana: Establishing the link based on empirical evidence. Sahara: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 2, 188–202.

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., DeLaFuente, J. R., & Gran,t M. (1993) Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addiction, 88, 791–804.

Sebit, M. B., Tombe, M., Siziya, S., Balus, S., Nkomo, S. D. A., & Maramba, P. (2003). Prevalence of HIV/AIDS and psychiatric disorders and their related risk factors among adults in Epworth, Zimbabwe. East African Medical Journal, 80, 503–512.

Shaffer, D. N., Njeri, R., Justice, A. C., Odero, W. W., & Tierney, W. M. (2004). Alcohol abuse among patients with and without HIV infection attending public clinics in western Kenya. East African Medical Journal, 81, 594–598.

Shisana, O., Rehle, T., Simbayi, L., Parker, W., Bhana, A., & Zuma, K. (2005). South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour And Communication Survey 2005. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press.

Simbayi, L. C., Kalichman, S. C., Jooste, S., Mathiti, V., Cain, D, & Cherry, C. (2004a). Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV infection among men and women receiving sexually transmitted infection clinic services in Cape Twon, South Africa. Journal of Alcohol Studies, 65, 434–442.

Simbayi, L. C., Kalichman, S. C., Skinner, D., Jooste, S., Cain, D., & Cherry, C. (2004b). Theory-based HIV risk reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 31, 727–733.

Simbayi, L.C. Mwaba, K., & Kalichman, S. (2006). Perceptions of STI Clinic Attenders about HIV/AIDS and Alcohol as a Risk Factor with regard to HIV Infection in South Africa: Implications for HIV Prevention. Social Behavior and Personality.

Talbot, E. A., Kenyon, T. A., Moeti, T. L., Hsin, G., Dooley, L., & El-Halabi, S. (2002). HIV risk factors among patients with tuberculosis—Botswana, 1999. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 13, 311–317.

Taylor, M., Dlamini, S. B., Kagoro, H., Jinabhai, C. C., & de Vries, H. (2003). Understanding high school students' risk behaviors to help reduce the HIV/AIDS epidemic in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of School Health, 73, 97–100.

Tengia-Kessy, A., Msamanga, G. I., & Moshiro, C. S. (1998). Assessment of behavioural risk factors associated with HIV infection among youth in Moshi rural district, Tanzania. East African Medical Journal, 75, 528–532.

UNAIDS. (2006). 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

Wechsberg, W. M. (2005). The Pretoria women's health co-op study. South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU): Monitoring Alcohol and Drug Trends. Tygerberg, South Africa: Medical Research Council.

Wechsberg, W. M., Luseno, W. K., Lam, W. K. (2005). Violence against substance-abusing South African sex workers: Intersection with culture and HIV risk. AIDS Care, 17, S55–S64.

Weinhardt, L. & Carey, M. P. (2001). Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Annual Review of Sex Research, 12, 125–157.

Weir, S. S., Pailman, C., Mahlalela, X., Coetzee, N., Meidany, F., & Boerma, J. T. (2003). From people to places: Focusing AIDS prevention efforts where it matters most. AIDS, 17, 895–903.

Wilson, D., Chiroro, P., Lavelle, S., & Mutero, C. (1989). Sex worker, client sex behaviour and condom use in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS Care, 1, 269–280.

Yadav, G., Saskin, R., Ngugi, E., Kimani, J., Keli, F., & Fonck, K. (2005). Associations of sexual risk taking among Kenyan female sex workers after enrollment in an HIV-1 prevention trial. JAIDS, 38, 329–334.

Zachariah, R., Spielmann, M. P., Harries, A. D., Nkhoma, W., Chantulo, A., & Arendt, V. (2003). Sexually transmitted infections and sexual behaviour among commercial sex workers in a rural district in Malawi. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 14, 185–188.

Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expressions and biological bases of sensation seeking. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zuma, K., Gouws, E., Willaims, B., & Lurie, M. (2003). Risk factors for HIV infection among women in Carletonville, South Africa: Migration, demography and sexually transmitted diseases. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 14, 814–817.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalichman, S.C., Simbayi, L.C., Kaufman, M. et al. Alcohol Use and Sexual Risks for HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic Review of Empirical Findings. Prev Sci 8, 141–151 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2