Abstract

In 1998, outbreaks of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection were reported in children attending Al-Fateh Hospital in Benghazi, Libya. Here we use molecular phylogenetic techniques to analyse new virus sequences from these outbreaks. We find that the HIV-1 and HCV strains were already circulating and prevalent in this hospital and its environs before the arrival in March 1998 of the foreign medical staff (five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor) who stand accused of transmitting the HIV strain to the children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Almost half of the 111 children studied in the early months after the discovery of the outbreak showed evidence of both HIV-1 and HCV infection1. Of 418 children eventually affected by these viruses, 248 were referred to European hospitals1,2. Sequence analysis of 51 children classified the HIV-1 infection as the strain CRF02_AG; HCV infection was classified as genotype 4 or subtype 1a in 15 children1,2.

We studied HIV-1 gag gene sequences from 44 affected children, plus 61 HCV E1E2 gene sequences that span the HCV hypervariable region (for methods, supplementary information). By using these data in an evolutionary analysis, we could place a real timescale on the transmission history of the outbreaks.

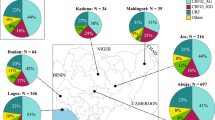

We collated all available reference strains that were closely related to the sequences from the Al-Fateh Hospital, then estimated and assessed phylogenies using algorithmic, bayesian and maximum-likelihood methods (for details, supplementary information). The HIV-1 sequences from the hospital form a well supported monophyletic cluster within the CRF02_AG clade, indicating that the outbreak arose from one CRF02_AG lineage. The cluster is closest to three west African reference sequences (Fig. 1a), the basal location of which suggests that the Al-Fateh Hospital lineage arrived in Libya from there. The branch length leading to the Al-Fateh Hospital cluster is perfectly typical; hence the Al-Fateh Hospital strain is not unusually divergent2.

a–c, Estimated maximum-likelihood phylogenies for HIV-1 CRF02_AG (a), HCV genotype 4 (b) and HCV genotype 1 (c). Source of sequences used for analysis: AFH, red; Egypt, green; Cameroon, blue. Black circles mark the common ancestor of HCV subtype 4a and 1a; numbers above AFH lineages give clade support values using bootstrap and bayesian methods, respectively. Scale bar units are nucleotide substitutions per site. For visual clarity, AFH clusters are represented by triangles and some non-informative reference strains are excluded.

In an equivalent HCV phylogenetic analysis, the HCV sequences from the hospital formed three monophyletic clusters containing 11 subtype-4a sequences, phylogenetically placed among Egyptian subtype 4a lineages; 22 sequences most closely related to a Cameroonian genotype-4 strain; and 24 sequences belonging to the worldwide and prevalent subtype 1a; four remaining sequences belong to genotype 4 (Fig. 1b, c; see supplementary information).

Epidemiological linkage of the HIV-1 and HCV clusters from Al-Fateh Hospital with sequences from sub-Saharan Africa is to be expected, given the large number of migrants within or passing through Libya3; indeed, the Libyan authorities have expressed concern about the risk of introduction of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis as a result of this migration4. In addition, HCV genotype 4 is endemic to central Africa and the Middle East5,6,7, and subtype 4a is exceptionally prevalent in neighbouring Egypt8,9.

Virus sequences also contain temporal information about the date of origin and age of epidemics10. We therefore comprehensively analysed the evolution of the Al-Fateh Hospital clusters using an established bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach9,10 that appropriately accounts for estimation uncertainty. We estimated three parameter values for each cluster: the date of its most recent common ancestor; the probability that its most recent common ancestor was more recent than 1 March 1998; and the percentage of its lineages that already existed before 1 March 1998. (These values are conservative, because cluster origins could be older than the most recent common ancestor, but not younger.) To avoid model selection bias, we used a range of applicable models.

We found that, irrespective of which model was used, the estimated date of the most common recent ancestor for each cluster pre-dated March 1998, sometimes by many years (Fig. 2).

In most analyses, the probability that the clusters from the Al-Fateh Hospital originated after that time was almost zero (for details, supplementary information). For the three HCV clusters, the percentage of lineages already present before March 1998 was about 70%; the equivalent percentage for the HIV-1 cluster was estimated at about 40%.

Our results support the existing nosocomial transmission scenario1,11 and suggest that Al-Fateh Hospital had a long-standing infection-control problem. The earlier origin and greater number of HCV clusters than HIV-1 clusters reflect the higher transmissibility of HCV compared with HIV-1 by such routes12. Crucially, we have shown that the HIV-1 and HCV strains responsible were being spread and transmitted among individuals attending the hospital before March 1998, indicating that many of the transmissions giving rise to the infection clusters must have already occurred before the foreign medical staff arrived.

References

Yerly, S. et al. J. Infect. Dis. 184, 369–372 (2001).

Visco-Comandini, U. et al. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 18, 727–732 (2002).

Human Rights Watch Stemming the Flow Vol. 18, No. 5 (2006); http://www.hrw.org/reports/2006/libya0906

European Commission Technical Mission to Libya on Illegal Immigration, 27 Nov–6 Dec 2004 (2006); http://www.statewatch.org/news/2005/may/eu-report-libya-ill-imm.pdf

Ndjomou, J., Pybus, O. G. & Matz, B. J. Gen. Virol. 84, 2333–2341 (2003).

Smith, D. B. et al. J. Gen. Virol. 78, 321–328 (1997).

Pybus, O. G. et al. Science 292, 2323–2325 (2001).

Frank, C. et al. Lancet 355, 887–891 (2000).

Pybus, O. G., Drummond, A. J., Nakano, T., Robertson, B. H. & Rambaut, A. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 381–387 (2003).

Drummond, A. J., Ho, S. Y., Phillips, M. J. & Rambaut, A. PLoS Biol. 4, e88 (2006).

Montagnier, L. & Colizzi, V. Report on the Benghazi Outbreak (2006); http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v443/n7114/extref/montagnier.pdf

Goldmann, D. A. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 110 (suppl.), 21–26 (2002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

description (PDF 397 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira, T., Pybus, O., Rambaut, A. et al. HIV-1 and HCV sequences from Libyan outbreak. Nature 444, 836–837 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/444836a

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/444836a

This article is cited by

-

A minimum principle for stochastic control of hepatitis C epidemic model

Boundary Value Problems (2023)

-

The inference of HIV-1 transmission direction between HIV-1 positive couples based on the sequences of HIV-1 quasi-species

BMC Infectious Diseases (2019)

-

Co-infections and transmission networks of HCV, HIV-1 and HPgV among people who inject drugs

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Science in court: Disease detectives

Nature (2014)

-

Viral phylogeny in court: the unusual case of the Valencian anesthetist

BMC Biology (2013)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.